Earthquakes, Tsunamis and Typhoons, Oh My!

My husband and I have a theory. It posits that any given person, when contemplating earthquakes, hurricanes and tornadoes, is ok with one, has a healthy fear of another and is absolutely terrified of the third. Growing up, as he did, in the midwest, earthquakes are not such a big deal to him, but hurricanes scare him to death. I, on the other hand, grew up in New England, where hurricanes hit but not hard. What scares the daylights out of me is tornadoes.

To be fair, however, our theory is incomplete. While it is true that I have recurring nightmares about tornadoes, I also have recurring nightmares about being covered by waves of water. My husband points out that, when I have these, it probably means I need to go to the bathroom. My worst nightmares involve water spouts -- tornadoes over water. I don't have them very often, but they are very consistent and consistently scary.

You might think, then, that the tsunamis that hit Samoa yesterday and the typhoons in the Philippines and Vietnam, with all of their flooding, would be very scary for me to contemplate. In fact, they probably would be, if I could bring myself to contemplate them, but I can't. And this is how I know that my fear of giant waves and of unrestrained water is actually not pathological.

If this were truly a dangerous phobia, I would hear about a tsunami and find myself thinking about it all the time. I would "live" it in my mind. It would trigger more nightmares. But in fact, I know my fears and have control of them sufficiently that I know not to do that. I can bring myself to imagine what the earthquakes in Indonesia and Samoa must have felt like, or the rain and winds from the typhoon in the Philippines and Vietnam. I can contemplate the death and destruction in all three places. But when it comes to the flooding and the tsunamis, I simply cannot see them happening in my mind's eye. I cannot put myself there. My mind is very good at protecting itself.

I was recently involved in a Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) where some of the participants kept talking about how awful the incident must be for others. They were saying things like, "I just keep thinking what he must be going through" and "I imagine how awful it is for her and I just cry all the time." My partner for the CISD had what I thought was a terrific way of responding to this. During the teaching phase, he said, "Let me suggest to you that you do not have to try on other people's trauma."

I am horrified and yes, a little terrified by what I see on the news today. But I know enough to know that I don't have to try it on to care.

What Makes Something Important?

Generally speaking, I blog about whatever heinous situation is dominating the news at the moment. Sometimes, that's a very easy event to spot. Generally speaking if it gets several columns on the front page of the New York Times, or more than one story on the splash page at CNN, you know it's "big." And if it's "big" and traumatic, it's stuff for the Quarterback.

Sometimes, however, it's not as obvious what is "big" in American media. Finding traumatic events is not much of a problem. Finding ones that seem compelling (and that I have something to say about) is sometimes harder. Today I had a particularly difficult time finding a story I wanted to blog about, so I started to reflect on what makes me think a story is "compelling." Sometimes the reflection isn't so pretty.

By my gut level definition, a story is compelling if it meets one or more of the following criteria, the more the better:

- the event is unusual

- the event affects people in an unusual way

- the event affects a group of people you might not think of as being affected

- the news coverage of the event raises a particularly interesting point

- the event affects people who I believe most people will identify with

There are two examples of this that became clear to me as I was desperately searching for a topic today. The first has to do with natural disasters. In my searching, I had skimmed over the deaths of hundreds of people in the Philippines during recent flooding, and decided I didn't have much to say. Somewhat later, a breaking news headline appeared detailing a very large earthquake near Samoa and a tsunami warning in New Zealand, and I caught myself thinking, "If there's a tsunami in New Zealand, then I'll have something to write about." Really? Deaths from natural disasters in the Philippines aren't compelling, but those in New Zealand are? How can I possibly assume that somehow people in the Philippines are "used" to this sort of thing?

Which brings me to my second example. Derrion Albert, 16, was beaten to death when he got caught in the conflict between two groups of students on his way home from school on Thursday. He was an honor student, a church-goer, and an innocent bystander. If this had happened in my hometown, it would be national news. But it happened in Chicago, and Derrion was black, and so it didn't make the news until a video of the beating surfaced, and we white folks could see that this is not a sort of violence you can ever "expect" or "get used to." But let's face it, privileged, suburban, white folks, of which I am one, still think of it that way.

All life is precious. We know that intellectually, but we can't seem to act like it. We distance ourselves a hundred different ways from trauma, whether to protect ourselves from the idea that it could happen to us or for more sinister reasons of racism, classism or xenophobia. If trauma happens to "those people," it doesn't happen to "us." But we are all those people, and they are all us. We probably won't make much progress in this world until we really believe that.

Can We Forget for a Minute?

Bob Greene has a commentary piece on CNN.com today about family annihilation. You may recall that this is the technical term for murders that wipe out a whole family, usually perpetrated by a member of the family. Greene expresses his concern that, as such homicides appear to become more common, we are becoming numb to them. He writes,

the willful and violent ending of a family's life must never become one more story at which we glance briefly and then turn the newspaper page or zap to another channel on the cable box or click to the next screen on our laptop. For if we lose our capacity to be shattered when this happens, then we have lost a part of ourselves.I would certainly share Greene's concern if I thought that we, as a society, were in danger of thinking that family annihilation was not so bad. It is so bad. The question is, do we have to find it so distressing?

Greene says we do. He makes a clear and Quarterback-esque argument for why family annihilation violates our worldview. As he explains,

we have always been taught: When there is nothing else, there is family. When, in times of the deepest despair, there is no one to lean on, there is family. Family is -- or at least should be -- the synonym for safety. Life's protective barrier against the world's dangers.He feels we should not lose that view of our families, and to fail to be horrified by family annihilation would be to give up on this fundamental sense of how the world should be.

I don't actually agree with Greene, at least not completely. There is a difference between saying that it is understandable that people are impacted by this kind of crime and saying it is necessary to be impacted by this kind of crime. I would argue that, in fact, there are times when putting something awful aside is not only OK, it's desirable.

The last thing we need is our society to come to a screeching halt because we are all so traumatized we can't function. We saw what that might look like in the days following 9-11 -- a tremendous sense of unity of purpose and a paralyzing fear that had us looking at everything as a potential threat. Eventually, we processed what had happened and put it to the side. We are different for having experienced that day, but we don't live every day with that kind of fear. I don't think we need to live every day with the kind of horror that really thinking about family annihilation brings, either.

Greene is mistaking overload for apathy. We are not at any risk of thinking that family annihilation is acceptable. When we choose to change the channel, we aren't saying we don't care. Sometimes, we're saying that we just can't take any more.

The Devil You Know

There's a wonderful young lady I know, a senior in high school whom we'll call "Hannah," mostly because being a senior in high school is hard enough without having your personal stuff splashed all over an adult friend's blog. At Hannah's school, on Monday, a threat was found written on the walls of the boys' bathroom. There's been no official word on what it said, but rumor has it it was something about how the school was going to "pay for this with lives." Parents were notified, and the school said they were sure there was nothing to worry about.

On Thursday, all afternoon activities were canceled, and before long word got out that another threat had been written on the bathroom walls. This time, people who saw it were asked not to tell what it said. Students were forbidden from bringing bags of any kind to school and had to walk through a metal detector on their way in on Friday morning. About half the students just didn't come.

Last night, my phone rang at 10:45 PM. That can only be a bad sign or a wrong number, and in this case it was the former. It was Hannah, calling to say that police had arrested a friend's boyfriend, a boy she knew but wasn't close friends with, on multiple felony counts for writing the threats. She was a little freaked out.

This turns my usual experience with crisis intervention on its head. Usually, I'm working with the people whose lives or whose loved ones' lives have been disrupted by the "bad guys." In this instance, that was true, but with the added layer that Hannah liked the bad guy, and didn't think he was bad, and didn't know what to think.

There's plenty here to overwhelm Hannah's usual ability to process information and "put it away," as we do with most things that upset us on a daily basis. If he did this, does that make her a bad judge of character, or a bad person? What about her friend, the suspect's girlfriend? And how must she be feeling? How can Hannah support her? What would it be like if Hannah's boyfriend had done this? Is the suspect really violent, or did he make a bad choice? How could he have ruined his life like this? If he could do this, and he seems like a regular person, does that mean that any regular person could do this? Could Hannah? Was she ever in danger from being around this guy? Is it OK to feel relieved that the scary situation at school has been resolved, if the way it was resolved hurts people she cares about? What happened to the sense of security she had about her school? About being with friends? If this guy was dangerous, how would she know who else was?

And this was before the shock wore off.

As we rush to help the victims of trauma and their families, it's sometimes easy to forget that the perpetrators have families and friends, too. Their trauma exposure is different, but it is there, and it is complicated. I told Hannah that she was asking all the right questions, and to give herself some space to not have the answers right now. We also talked about the disturbing realization that if this boy could make such a bad choice, she could too. I encouraged her to remember that while she could have, she didn't. In the words of Albus Dumbledore,

It is our choices that show what we really are, much more than our abilities.

Post-script: Amusingly, in the middle of our conversation, Hannah said, "I'm supposed to be drinking water, aren't I?" I had once told her about a colleague doing an intervention on the phone and telling the person to drink a lot of water, both to help flush out the stress hormones and to give the person something to do. Hannah remembered -- it was a case of unintentional pre-incident inoculation.

Domestic Violence and Suicide Among Our Finest

On Tuesday morning in the parking lot of the Canton, Michigan library (the next town over from me), a Detroit Police Officer shot and killed his wife, who was also a Detroit Police Officer, and then killed himself. The back-story is a distressing one. The wife had come to the police department to file a complaint and changed her mind a few days before. Then police were called to the home for a domestic dispute, only to find the home empty and a note from the husband directing who should get his possessions if anything happened to him. Canton police contacted Detroit police, who made contact with the officer and decided everything was OK. Two days later, both he and his wife were dead.

It's tempting to play the blame game here. I'm sure there are plenty of people who are pointing fingers at one another. I am going to resist getting sucked into that. But this is a good opportunity to take a look at two phenomena that this incident illustrates: suicide among law enforcement personnel and domestic violence among law enforcement personnel. Both are significantly elevated.

The suicide rate among working men in the United States is roughly 12 per 100,000. Among officers in the New York City Police Department, it is 15 per 100,000. The rate in Detroit department is 28 per 100,000. Why is it so high?

Police officers in general have characteristics that put them at higher risk for suicide. They are disproportionately younger men. They are under psychological stress. They are in a culture that frowns upon open discussion of feelings and may penalize officers for seeking mental health care, effectively reducing their access to help. They are exposed to trauma. And they have easy access to a firearm. Anyone with these characteristics, regardless of profession, is at elevated risk for completing a suicide.

Detroit police officers seem to have a rate that is elevated even above that. The job of a Detroit officer is probably more stressful than average. The city is in horrific financial trouble, endangering their jobs on an ongoing basis. The crime rate is high. The poverty rate is high. I would guess that the ratio of "easy" calls to traumatic ones is much worse than in other major cities. They are the guards for a dying city -- they don't really have much hope that their efforts are making the city better. All of that increases the psychological stress of the job.

Perhaps more importantly, however, as far as I can tell there is no Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) support for Detroit Police Officers. New York City has a CISM team -- that may account for the difference. That not only means that Detroit officers are not getting appropriate intervention for trauma exposure, but it probably also reflects a department culture that frowns even more on seeking mental health assistance. These men and women are traumatized on a daily basis, and they probably aren't getting much help.

The exposure to violence that all officers have probably also accounts for the increased incidence of domestic violence in marriages that involve a police officer. We know that trauma exposure makes people irritable. Seeing violence also desensitizes people to violence. And spouses of police officers are even less likely to report their abusive partners than most battered spouses, because they are afraid of angering their spouse even more by possibly costing them their job, and because they fear that police officers will not take complaints against one of their own seriously. There isn't much to suggest that domestic homicides are higher among police officers, but domestic violence certainly is.

And so we wind up with the scene outside the Canton Library. I said I wouldn't point fingers, and I won't, at least not in the traditional sense. But I will say that I wonder what might have been different if Detroit was taking better care of its finest.

Thanks to Quarterbacker Maureen for the tip. Although this incident occurred less than 10 miles from my house, the demise of our local newspaper over the summer meant that this was not covered on the "replacement" website, or even on most of the general Michigan news websites.

Death By Politics, Fear By Media

Bill Sparkman, 51, was found hanging from a tree in rural Kentucky on September 12. As far as anyone knows, he was working his second job as an interviewer for the Census Bureau. Authorities are not 100% sure whether it was a suicide or a homicide. This kind of thing happens with some frequency, and so it's not surprising that it did not make national news at the time. The Associate Press didn't pick up the story until yesterday, when it reported that Sparkman had the letters "FED" written on his body when it was found, raising suspicions that he was killed because of his job with the Census Bureau.

Occam's razor tells us that the simplest explanation is the most likely one. Even if we presume that Mr. Sparkman was murdered, the most likely scenario is that he happened upon someone who didn't want to be happened upon. The area where he died has a lot of methamphetamine activity, and it's not hard to imagine him knocking on the door of a meth lab and/or a house inhabited by someone high on meth, who killed him and wrote "FED" as a way of being mocking. That scenario is horrible, but, frankly, it isn't why this has made the national news.

What people are really interested in and worried about is the possibility that Sparkman was murdered not for happening upon the wrong people, but for doing his job. It could be that someone murdered him because they didn't think the government should be asking questions, or because they just didn't like the government. Some on the political far-right have recently expressed great distrust of the 2010 census. Maybe Sparkman was murdered by someone who thought this way.

This is a sensationalistic possibility, and reporters can usually dig up someone who makes the sensational seem very real. The AP found a waitress near where Sparkman was killed, who said,

Sometimes I think the government should stick their nose out of people's business and stick their nose in their business at the same time. They care too much about the wrong things.And of course the article makes it seem like this was her answer to what she thought about the murder. More likely, it was her answer to why someone would not like the census.

The notion that someone is killing governent workers because they work for the government is fundamentally frightening to a lot of people. If, in general, you think that the United States government is, if not a force for good, at least a necessary evil, the targeting of government workers in an attempt to protest their work makes you worried for the safety of the country, and for your own safety by extension.

But the fact remains that it is far more likely that Sparkman was killed because of where he was, not who he was. And even if he was killed for working for the census, it is more likely to be the work of a single fanatic than representative of any organized movement. But that's boring, and boring doesn't get the attention of the press. Let's hope, however, that boring wins out in the end.

Dying on the Phone: The Georgia Floods

Nine people thus far have died in flooding in Georgia. That is truly awful, and it certainly has made the news. These are nine human beings who are not going home to their families. That is worthy of our attention. But does it always get it?

If nine people died in a random shooting at a mall, it would be all over the news. We would be interrupting our regularly scheduled program for round the clock coverage. If they died in a terrorist bombing in an American city, there would be nothing else in the news. If they died in a bombing in an Iraqi market, it would be a passing mention.

I am as guilty of making these distinctions as anyone else. We care most about things closest to us and most violating of our expectations and world view. The idea that flooding is dangerous is easier to accept than the idea that shopping in the United States is dangerous. We already knew that shopping in Iraq was dangerous. So I, like most of you, greeted the news out of Georgia with a click of my tongue.

Then, however, I read a story about one of the women who drowned. She was literally on the phone with 911 as the water came into her car, which had been swept away in a flash flood and stuck in some trees. She was on the phone when she died. You can read about it online, and you can listen to the 911 call.

Maybe you shouldn't.

First of all, our society usually accepts that someone's death is a private thing, or at least a family thing. There is a voyeuristic feeling to listening to someone dying, and I'm saddened that the authorities chose to release the call.

Second, 911 dispatchers will tell you that listening to someone in great distress is traumatic. You know they need your help and you are powerless to help them. While listening to the tapes after the fact is less distressing because we know how it is going to end and we don't expect that we will help the caller, it is still the witnessing of a traumatic death, just as surely as watching it would be. None of us need that exposure. Some of us will truly be disturbed by it.

The 911 call brings this victim out of the expected and into the unexpected. We know that people die in floods. We don't like to think about how exactly that happens. We allow ourselves to think that it's just "one of those things." But in reality, this week it was nine of those things, each one with its own story and its own traumatic truth.

Another Family Gone

Five members of a single family in Beason, Illinois were found dead late Monday, and a small child is in the hospital. Do you have the feeling you've heard this story before? I did when I saw it. Another family was murdered in Florida over the weekend. And one in Virginia. And Georgia a few weeks ago. It seems like this is happening a lot lately.

I started searching online for statistics relating to this phenomenon, and while I didn't find what I was looking for, I did learn a lot. First off, there's a name for the phenomenon of a family member killing the whole family -- "family annihilation." There are typically 16 to 20 such murders in the US per year. They are most often committed by the male head of household, and are consider an extreme form of domestic violence. Not all of the recent cases fit this profile, but a number of them do.

These cases catch our attention, but they don't seem to capture our fear the way some other ones do. This phenomenon is interesting to me, because protecting one's family is a very dearly held value for most people. Why aren't we afraid? To understand that, we have to understand what makes us afraid in the first place.

We are afraid when we fear for our own safety. But most of these cases don't cause us to fear for our safety, because the crimes are often committed by members of the same family who dies. Roughly 50% of all homicides in the United States are committed by someone known to the victim. When you have multiple victims, the numbers would seem to indicate that the perpetrator is known to one or more of them. And who knows a family better than . . . a family?

One headline from the story out of Illinois caught my attention. It read "Five Dead and Town Told to Lock It's Doors." My first reaction was that this was silly -- if the family was dead, wasn't it a family member who did it? Obviously the police would know more about that than I, and if they said to lock your doors you probably should (and that's not even addressing my astonishment that there is anyplace left in this country where people don't lock their doors all the time).

The fact of the matter is, these things don't scare most of us because we think it can't happen to us. It is certainly true that there are usually warning signs before a family member goes to this extreme of violence. But even those who live with an abusive family member don't think they will become a statistic like this. We might be better served to pay more attention to those around us, and to lock our doors with violent family members on the other side of them.

Can We Have Our Tragedy Back Now?

Annie Le's body is finally back in her hometown of Placerville, CA, a week after her body was found in the wall of a Yale lab building where she did her research. Services will be private. Her brother, Chris, gave an interview to a local TV station, in which he expressed some frustration with the media:

We just want the media to respect our privacy. We have a lot of stuff to do. This makes it all the much harder.

The Le's have the unenviable task not only of burying a family member who died traumatically, but of trying to sort out this incident that is uniquely theirs while there is an entire country of people who think it belongs to them.

Annie Le's murder captured the attention of media outlets all over the country, and with them all of their readers and viewers. On the day the suspect in her murder was first named, his name was the top most searched term on Google, and at least 3 other of the top 100 were related to Le and the investigation. We all feel like her death is our tragedy.

But it isn't. Most of us had never heard of Annie Le before she went missing, and had she not been killed we never would have. Our fascination with her case has absolutely nothing to do with her as a person, only with the circumstances of her death. And many of us think we are entitled to spout off theories about her and what "really" happened. Rumors run rampant about her killer, whether she had a romantic entanglement with him, what she might have said to put him over the edge, whether he was stalking her, and on and on.

That's not what her family wants to be thinking about right now. They want to deal with their grief and their trauma reactions, and they want to remember her as she was to them. As her brother said,

Make no mistake about it, part of the trauma the Le family has to process now is the trauma of having complete strangers meander through their loved one's life, speculating, intruding, and saying any foolish thing that comes into their head. When they ask for privacy, they aren't just asking us to stop trying to interview them. They're asking for us to stop talking about this incident like we know anything because, from their point of view, we certainly don't.She lived a good life. we want to respect that and have others respect that as well.

Is it Ever OK to Lie to Prevent Panic?

On CNN this morning, President Obama talked about his family's plans for H1N1 prevention. He said that the "Obama Family Plan" is to

call up my Secretary of Health and Human Services, Kathleen Sebelius, and my Centers for Disease Control Director, and whatever they tell me to do I will do.He continued on to say that he intended to be vaccinated, but that he understood that he was not in a high risk category:

We want to get vaccinated. We think it's the right thing to do. We will stand in line like everybody else. And when folks say it's our turn, that's when we'll get it.He said he expected that his daughters would receive the vaccine first, and "I suspect that I may come fairly far down the line."

On the face of it, this is a fairly masterful piece of crisis communication. Through his example, Obama conveyed three important messages:

- Follow the current recommendations of HHS and the CDC, whatever they are,

- Get vaccinated and,

- You may have to wait for a vaccine, and it's important to let those more high risk than you go first.

There is one thing, however, that truly bothers me about this response, and that is that it is almost certainly not true. I completely believe that Obama is going to follow the HHS and CDC recommendations and that he intends for his family and him to be vaccinated. What I don't believe for an instant is that he is going to wait for the vaccine.

For the record, I am not arguing with whomever is going to make the decision if they think the President should get it early. While he is at relatively low risk of dying from H1N1, his death is a very high risk event for everyone else. If he gets the vaccine first, it's fine with me.

So the question is, how do I feel -- how do you feel -- about him lying about it. One major rule of crisis communication is that you don't lie, even if you think people shouldn't know about something. That's because when your lie is found out, no one will listen to you on anything else. On the other hand, it's a lot more difficult to convey that people should wait their turn for the vaccine when your turn is on a completely different system than everyone else's.

In July, President Obama was asked if he would like to be covered by his proposed health insurance plan, and he said,

You know, I would be happy to abide by the same benefit package. I will just be honest with you. I'm the president of the United States, so I've got a doctor following me every minute which is why I say this is not about me. I've got the best health care in the world. I'm trying to make sure that everybody has good health care, and they don't right now.This is the sort of answer I would have preferred him to give to the H1N1 question. He could have said,

We will go with the recommendations of the CDC and HHS. That most likely means that we will be vaccinated. And because I'm the President, the secret service may well have their own ideas of when I should be vaccinated. But if they tell me to wait, I will wait, because I know that people in my age group are fairly low risk.You can argue that technically he didn't lie -- he said he would follow the recommendations and get vaccinated "when it's our turn." I think that would have more credibility if he acknowledged that his turn is likely before almost anyone else's.

Do Now, Blame Later: Phillip Arnold Paul on the Loose

Phillip Arnold Paul has paranoid schizophrenia. In 1987, he killed a woman because he believed she was a witch and was committed to Eastern State Hospital in Medical Lake, Washington, about 20 miles south of Spokane. On Thursday, he went with a group of patients on a field trip to the Spokane Interstate Fair. Sometime around 11:30 AM, he walked away from his group, and he hasn't been seen since. This is not good.

What makes it doubly not good, however, is that there seems to be no coordinated effort to keep the public informed. I'm not in Washington, so I can't say for sure, but looking over the news reports from the last few days I see no reference to a press conference, no official statement, no news release. There is information out there, but it is very much not clear who is in charge and what they are doing.

Actually, that's not true. One thing that authorities clearly are doing is blaming each other. The union that represents workers at the hospital says that they warned about these field trips. The Secretary of Health and Human Services for Washington has hit the airwaves announcing a review of the policy that allowed Paul out in the first place. The Sheriff's Department has let it be known that they are pretty mad at hospital officials, who didn't report the escape for more than an hour. The Governor has criticized the trip. The hospital says they acted according to policy and taken this trip before. The organizers of the fair say they didn't know about it.

I'm not saying there isn't anything to criticize here, although I'm certainly not in a position to say what the policy ought to be. What I am saying is that criticism of the policy is not what the public needs to hear right now. There is a time and a place for infighting. What the public needs is to put this situation in some context and to understand just exactly how much of a threat they are under. They also need to feel somewhat confident that authorities are going to catch this man. For that, officials are going to need to present a united front.

Here's what should be happening. The communications officer for the incident command (and I sure hope they are using the Incident Command System to organize this) needs to hold a Crisis Management Breifing, which can be watched remotely by the public. He or she needs to stand up in front of the press, with representatives from the Fair, the hospital, the Sheriff's Department, the State Police, and the Department of Human Services, and make it clear that finding Paul is their number one priority. They should say that they have halted field trips (which they have) until the policy can be reviewed, which will happen as soon as they apprehend Paul. They need to detail all the various things they are doing to find him. They need to give information about his current mental state, so the media doesn't need to rely on old court documents that may or may not apply, and about how stable he is and for how long.

There will come a time for a thorough investigation. There will come a time when everyone can point fingers to their hearts' content. Now is not that time. That energy needs to be devoted to finding this guy. People can get fired for the escape later.

Sometimes trauma has a Little t

My daughter tells me it wasn't a year ago, it was a year less 11 days, but to me it was exactly a year ago, because it was the day before Rosh Hashanah. My secretary walked right into a meeting in my office -- something she never does -- and told me that my daughter was on her way and had hurt her wrist. I walked into the main portion of the office and peeked out the window at my 10 year-old, whose cries I could already hear. I could see her walking with a friend, her arm poking out of her sweater with her wrist looking curved in all sorts of places that wrists are not supposed to curve. It was obviously broken. She had fallen off the monkey bars on the playground and landed on her arm. As it turned out, her arm was broken in the wrist and above the elbow. She required surgery that night and two days in the hospital, with me sleeping on the couch beside her.

Was this a critical incident? Hard to say. A critical incident is one which has the capacity to overwhelm your usual coping skills. This was certainly more obviously a trauma for my daughter than for me, but at the same time it was more emotionally distressing to me than it was to her. She wasn't scared so much as she was wanting the pain to stop. I was scared for her and coping with the violation of my belief that I could protect my children from harm.

The first clue that this incident overwhelmed my coping skills comes when we compare this incident to one that happened a couple of weeks earlier. Another child came in from the playground having fallen from a swing, his arm also obviously broken. While the office manager called the father, I worked with other staff to carefully immobilize the arm so dad could safely take the child to the hospital. When my own daughter was the victim, however, I simply grabbed my purse and ushered her to the car. I didn't assess the injury, I didn't splint it, and I left my keys on my desk inside. When the ER resident put her x-rays up for me to see I was horrified, both because of how graphic the elbow break was and because it was clear that I should not have driven her myself, and certainly not without immobilizing the injury.

Another hint that this was traumatic for me is the vivid sensory memories it holds. I can play it in my mind like a slideshow: the sight of her wrist . . . the sound of her begging me to touch her fingers in the car because she couldn't feel them . . . the feeling of lifting her into the wheelchair . . . the scene of them cutting off her sweater . . . the sight of the x-rays . . . the sound of her teacher on the phone saying, "if I could have flown across the playground, I would have caught her" . . . the smile on the doctor's face after surgery . . . the taste of the dinner my friend brought me . . . the sight of the "relaxation station" the hospital placed by her bed with gentle lights shining in the darkness.

If you ask my daughter about that day, she talks about it fairly calmly. If you ask me, I shudder visibly. It was worse for her physically, but for me emotionally. It's a good reminder that the people most impacted are not always who you might think, that sometimes trauma isn't Trauma, and also . . . be careful on the monkey bars.

May all the Quarterbackers out there be inscribed for a sweet, healthy, happy and trauma-free New Year.

Tashawnea Hill: Won't Somebody Think of the Children?

Some of the facts are not in dispute. Tashawnea Hill, a 35 year-old army reservist, was taking her 7 year-old daughter to dinner at a Cracker Barrel restaurant in Poulan, Georgia on the evening of September 9. A White man was coming out of the door when Hill, who is African-American, and her daughter were about to go in, and Hill believed that he almost hit her daughter in the face with the door. She exchanged words with the man, and he beat her in full view of her daughter.

The only facts in dispute are what exactly Hill said to the man, whether, as he alleges, she spit on him, and whether, as she alleges, he shouted racial and sexist epithets at her as he beat her. The FBI is investigating this as a hate crime, and the police say that witness statements and surveillance footage indicate the attack was unprovoked.

The man who beat Ms. Hill is charged with misdemeanor battery and disorderly conduct. He is also charged with cruelty to children even though everyone agrees he did not hit the daughter. Let's hear it for Georgia law enforcement for understanding that damage to children doesn't necessarily require physical contact.

The police report described the daughter's reaction in vivid terms. When officers arrived, she was

crying uncontrollably and her body [was] shaking/trembling.

This is a very typical reaction for a child -- and for an adult -- who has witnessed a traumatic incident. In addition to watching her mother be attacked, this girl has to have feared for her own safety. And where does a 7 year-old run when her mother is being beaten? Where does she believe is safe? Probably nowhere.

I've written a lot in this space about the way trauma violates our world view. In this instance, that is doubly the case. While Tasha Hill knew before September 9 that the world can be dangerous, but probably did not operate with that in the front of her mind day in and day out. Her daughter, at 7, was most likely at a stage where she believed her mother was powerful and would keep her safe. Little kids scare more easily than adults, but they also fundamentally think adults can protect them. When this girl saw her mother beaten, she was suddenly and shockingly exposed to the danger her mother was in and the fact that her mother could not keep that danger away from her. That's a big lesson for a little girl.

And of course, that's without dealing with the obvious other ways this incident will affect Ms. Hill's daughter. She not only saw her mother attacked, but she allegedly saw her attacked for being an African-American female. That has to have an impact on a little African-American girls' sense not only of safety but of self esteem and self worth. The bottom line is, if I were she, I'd be shaking too.

Driving a Desk

Before last June, there hadn't been an officer-involved shooting in Miami Beach, FL since 2003. In a single week in June, there were two. But that's not what makes this situation noteworthy. What's noteworthy is that the same police officer, Officer Adam Tavss, was involved in both shootings, which occurred just 4 days apart. Tavss was taken off the street for 72 hours following the first shooting. The families of both of the dead men are asking the Justice Department to investigate the situation, and why Tavss was allowed back on the street so quickly.

It might be a good idea, then, to review the thinking behind taking an officer off the street when there has been an officer-involved shooting. After all, if we don't understand why someone is taken off the street, it's hard to assess when they should go back. There are a number of reasons.

- Avoiding Lawsuits: There is a general understanding that if a police officer who has just shot someone shoots someone else, the department is opening itself up to legal scrutiny. That is exactly what happened in this case. Pragmatically, departments like to play it safe.

- The Officer Isn't Safe: Officers involved in a shooting, or any other traumatic incident, may experience memory loss, slow cognitive processing, depression and impaired decision making, just to name a few reactions. The person most at risk from this is the officer him or herself, since thinking slowly can be deadly on the street.

- Make Sure the Officer Isn't Trigger Happy: It is possible, although unlikely, that the officer really has impaired judgement to begin with, and that the first shooting was completely unjustified. The last thing you want is to put him back on the street and let him do it again.

- The Officer Might Scare Too Easily: If the officer is traumatized by the first shooting, which probably occurred because his life was in danger, he may be at a heightened state of alert and more likely to perceive that his life is in danger than someone who hasn't been through that. This may cause him to make the decision to use lethal force at a time when someone else would not.

Officer Tavss is under investigation, as is the department. A thorough investigation is always warranted when someone is killed, and it's worth asking whether Officer Tavss was ready to go back on the street when he did. But it bears remembering that keeping officers off the street after a shooting isn't just to prevent additional shootings, it's to protect the officer himself. It's always possible that the second incident was just a horrible coincidence, and still a justified shooting.

Violence on Campus

It's another Quarterback Truth-Telling Moment. What do you assume this post is going to be about? What current event comes to mind when you hear "violence on campus?" I'm guessing that, for those of you who have an answer, you're thinking about the murder of Annie Le, the Yale pharmacology graduate student. It's all over the news, with new suspicions and breaking stories several times a day. I blogged about it myself twice in one day this weekend.

Actually, the story that caught my attention this morning was the murder of Juan Carlos Rivera at about 9 AM at Coral Gables High School in Florida. I thought this would be big news, but it disappeared off the major news sites basically as fast as it appeared, and it made me wonder why. Why is the murder of Annie Le, and adult in a relatively large city, more newsworthy than that of Juan Carlos Rivera, a teenager in an suburban high school? In fact, the Internet community itself is debating a very similar question as we speak -- is the murder of Annie Le a big enough event to merit its own Wikipedia page, or is it just a flash in the pan.

My first hypothesis on this was that murder on college campuses is significantly less frequent than murder on K-12 campuses. A little rummaging turns up the fact that in 2004 (the most recent statistics I could find for both years) there were 15 homicides on college campuses in the United States, while in the 2003-2004 school year there were 22 homicides at K-12 schools. So yes, murder in a K-12 school is more rare, but not by much, and not when you consider that the total student population of colleges is significantly smaller than the student population of K-12 schools. This doesn't seem like the answer.

Part of the answer, I think, is that American society is quite captivated with weddings, what happens before weddings and what happens after them. The fact that Annie Le disappeared a few days before her wedding caught our attention, and once we were paying attention to the mystery, we weren't going to let it go. Part of the answer is probably also the mystique of an Ivy League College and an obviously bright victim.

Still, we as a society are usually really interested in school violence. The murder of Juan Carlos Rivera hit the national news this morning, I think, because it played to our deepest fears about our children's safety in school. The problem is that as soon as the press got more information about this murder, the victim suddenly didn't seem the innocent schoolchild we envision when we think about school violence. It turns out that Rivera was in a fight, reportedly over a girl, and the other student pulled out a box cutter and stabbed him. That defies our idea of what "school violence" is -- when we get scared about it, we get scared about random mass shootings and people from the outside coming in, not about fights.

More than that, though, we tend to have this idea that if someone is killed in a fight at a school, it must be at a school that is "used to" this kind of violence. While certainly there is more violence at some schools than at others, I don't think any school is "used to" students killing each other. Keep in mind, only about 20 kids in the whole country die this way each year. Violent death at a school where you work or study violates the generally true premise that school is a safe place and that the adults in a school can keep children safe. Keep in mind that children are twice as likely to be victims of a violent crime when they are not at school as they are at school.

Finally, and perhaps most disturbingly, Juan Carlos Rivera is not the quintessential "sympathetic victim" our society rallies around. He is male. He appears to have been somewhat violent himself, at least today. And, yes, he is Latino. And our gut intuitions about some schools being "used to" violence pales in comparison to what we assume to be true of violence in Latino communities. Few would have such a thought consciously, but that underlying racist assumption is reinforced daily in popular culture. Consciously or not, the press began with "this is big, a student was killed at school" and quickly reverted to "it was a Latino boy in a fight, that's not news."

At the end of the day, the Le family and the Rivera family have empty seats at their tables. Whether one victim is "sympathetic" or "deserved it" is really an offensive question. Their families don't deserve to be without their children, period.

How Do Little Kids Understand Tragedy?

A friend called last night to talk about her son. A daycare classmate's mother died unexpectedly this week, just days after a cancer diagnosis, and she knew her son would hear about it. What, she wondered, should she tell her own three and a half year old when he asked what that meant?

This is an understandably difficult situation. First of all, talking to children about traumatic events is always hard. Our first inclination is to protect them. We are afraid of scaring them, and we think if we just don't talk about it they won't be afraid. But we're wrong. Children know that something has happened -- in this case the classmate has told him. When we don't talk about it we send a very powerful signal that the topic is really horrible -- so horrible that we can't even talk about it. Children have vivid imaginations, and what they envision in the absence of good information is often much, much worse than what has really occurred.

In this instance, we have the added twist that the children involved are very young. They are old enough to hear the words and ask the question, but they don't really understand the concept of death. The classmate is demonstrating this when he so casually tells his friends that his mother died. He knows she is dead, and probably someone has explained what that means, but he doesn't have the experience or cognitive framework to understand it. Kids at this age do not understand the concept of time very well, and they don't understand what "never" and "forever" mean.

The words we often use to explain death to young children can actually make their understanding harder. When we say, "she went to sleep and will never wake up" the child understands that sleeping is a dangerous thing. When we say, "God wanted her to come be in heaven," they don't think God is very nice. It is quite a trick to come up with a way to explain this that is both comprehensible to young children and not even more frightening than it needs to be.

It happens that my friend's dog died a while back, and they had told her son that he went up to heaven with God. Based on this, I suggested she explain the current situation to him this way:

Billy's mommy got very very very very very very very very very very sick. The doctors tried to make her better but they couldn't, and her body stopped working, so she went up to heaven to be with God.Note the enormous numbers of "very's." Children, particularly young children, are concrete thinkers. If you tell them that Billy's mommy got sick, then when they or their parents are sick with a cold, they may be afraid they will die. They have no conception that certain types of sick can kill you and others usually don't. By putting lots of "very's" in the explanation, you create a way to talk about this. If they express concern about their cold, you can say,

Yes, I'm sick, but I'm not very very very very very very very very very very sick.Now your child will know what that means.

I also warned my friend that her son may be totally unaffected by this. He may not make the connection at all that if his classmate's mommy died, his mommy might die too. Children at this age are still very egocentric. Everything in the world has to do with them. Their mommy has absolutely nothing to do with someone else's mommy, because they don't really understand the relationship between their classmate and their classmate's mommy. I told her not to be surprised if her son seemed fine. This afternoon she emailed to say, "He totally didn't get it."

It was also possible, of course, that he wouldn't be fine. He could have processed, on some level, that this is bad and scary. If so, he might have nightmares or trouble sleeping, regress in his potty training, be more cranky or lose his appetite. All of that would be nothing to worry about unless it lasted a long time. In the meantime, he needs his parents to cuddle him and reassure him and validate his feelings. We can all use that sometimes.

As my friend's son gets older, he may revisit this incident in different ways. With each developmental stage, he may, reprocess it based on his new understanding of what death means and what his mommy means to him. More than likely, however, he won't remember this at all -- he's awfully young. His friend may not remember it either, although he, of course, will grow up with the impact of not having his mother. That's another journey altogether.

You can find more tips on talking to children about traumatic events here.

Update: Annie Le

Earlier today I blogged about Annie Le, the Yale grad student who went missing five days before her wedding. I wrote about how hard it is to respond to an incident that does not have a clear end to it.

As you may have already heard, a body presumed to be Le was found in the walls of the building where she was last seen. Now the incident has an end, and the hard work of dealing with it falls to her fiance, family and friends. I wish them well, and send my deepest sympathies.

Annie Le's Wedding Day: Who Could We Help, and How?

Yale pharmacology graduate student Annie Le was supposed to get married today. Instead, her fiance is in New Haven, trying to help law enforcement officials figure out where she is and what happened to her. She was last seen outside the Yale medical school on Tuesday. Her keys, purse and cell phone were all left in her office. She doesn't have a car. Friday brought word that a Professor whose class she was to take Tuesday afternoon, and who canceled class abruptly on that day, was being interviewed. Evidence was removed from the med school building yesterday, and unofficial, unconfirmed reports say that evidence was bloody clothing found in the drop ceiling of the lab in which she worked. Police say they don't think she ran away.

This has got to be gut-wrenching for her fiance, family and friends. The twists and turns are coming quickly, but no resolution is in sight. While everything I've detailed here is true, it's entirely possible some or all of it is irrelevant. The reports regarding the clothes could be false, or they aren't hers. The Professor could have gotten the stomach flu. Clues give hope for figuring this out, but they don't make the waiting much easier.

From a crisis response point of view, this is also incredibly tricky. It's not that no one needs help, it's that it's not at all clear who we should be supporting or how we would go about doing it. We're supposed to respond after the event is over. This one isn't, but it's in a new stage. We've moved from "she'll turn up" to "something happened to her," but we don't know that for sure and we don't know what it was. We also don't know if she's alive. And worse, it could be we will never know. At what point do we decide that it's time to help out anyway? Or is this one of those incidents when help will never come, because there will never be a time we can say it's over?

What particularly gives me the creeps, however, is the notion that if, at some point, we decided it was time to try to offer some early crisis intervention to those affected -- and there have to be a lot of them, including everyone who goes to school or works there -- there is a significant possibility we'd be working with the person or persons responsible for her disappearance. Now, there are times when working with the person responsible for an event is more than appropriate. I'm thinking, for example, of the person who ran a red light and caused a fatal car accident. But there, their level of culpability is out in the open. Here, we'd be working with someone who is simply lying to us. And the thought that there would be the remotest possibility of learning something during the course of the intervention that the police did not already know is horrifying. We promise confidentiality, but privilege has not been established. I don't want to be in that position.

All this, I suppose, is why you wait until the event is over to respond. It's just much easier to do that when the event has a clear beginning, middle and end. The current endless middle is hard for us. It has to be a zillion times harder for Annie Le's friends and family and the Yale community. I hope they get their resolution soon, and I hope against hope that she comes home safe.

Terror(?) on the Potomac

Yesterday, September 11, at about 9:30 AM, CNN breathlessly reported that Coast Guard boats and a helicopter were apparently confronting a suspicious vessel in the security area of the Potomac River, near where the President was commemorating 9/11 at the Pentagon. The reports escalated -- the vessel had been fired upon. Cable news and the Internet picked up the story.

It was a training exercise.

Let the finger-pointing begin. CNN reported an interpretation of what they heard over a scanner picking up the Coast Guard radio traffic, but apparently didn't think it odd that the report of gun fire began with the radio transmission, "bang bang bang bang." They say they called the Coast Guard and were told they were not aware of anything going on on the Potomac. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard says that they never coordinate their training exercises with other agencies, and they train like this all the time.

So what went wrong? If training exercises like this one are commonplace in that area, why did this one make national news? I bet you already know part of the answer. It was September 11. And yes, that matters, and no, it's not because we're all crazy.

The date itself -- September 11 -- is a trigger for most people in this country. The various commemorations on the news heighten that. And that's not a bad thing, necessarily. But it means we are all in a space where we are much more willing to believe that terrorists will attack the US. Most days we know it's a possibility, but on September 11 it feels like a likelihood. This exercise, and what CNN heard over the scanners, was therefore much more believable, and the lack of confirmation was less troubling. It might have been a good idea if the Coast Guard had considered this and announced the exercise, or held it on another day, or at least made sure it's own people could tell the press what was going on. There are two sides to every coin, though, and CNN should probably have known that both they and their viewers were more willing to believe the worst and more prone to panic yesterday than, say, the day before.

It's interesting to consider how long it will be before we are not so triggered by September 11. I see signs that it is fading already: A few years ago I was lambasted for holding a fire drill on that date. We had one yesterday, and no one said a thing. The edge has, at least a little, been taken off. But not so much that everyone can not worry about the impact of anti-terror exercises and erroneous news reports.

The Trauma of the "Other Side"

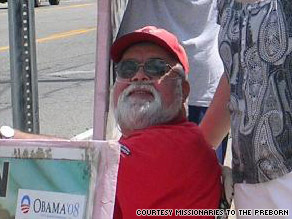

James Pouillon, age 63, was murdered today across the street from the high school in Owosso, MI. The same shooter allegedly also killed the owner of a local gravel pit, Mike Fuoss, 61. You've probably never heard of Owosso -- it's about an hour and a half from my house and I had never heard of it. You also probably have never heard of James Pouillon, although my understanding is that if you were from Owosso you probably would have.

James Pouillon was a prominent and vocal anti-abortion activist. He frequently stood near the High School holding graphic pictures of fetuses. Police say that the shooter was offended by material he had been displaying this week.

When you do a response to a traumatic event, you have to commit to leaving your politics at the door. A traumatized person is a traumatized person, and whether you agree with their politics or their life choices or whatever else has to be irrelevant. I have done interventions with people who talked about how only members of their religion were going to heaven, and the rest of us were going to hell. I have worked with people who drank to excess and did drugs and were irresponsible about their lives. I have helped teenagers who were clearly trying to provoke the adults by talking on their cell phones and chewing tobacco during a debriefing. And really, I didn't have much trouble with those.

But everyone has events that they should not be responding to. Sometimes, it's the nature of the incident that is the issue. I know tremendously well-respected responders who simply will not respond to the death of children, because they find it too upsetting. An event that is too close to a trauma in the responder's own life can be too much. Sometimes, you're just plain burnt out.

Then there are events that you cannot respond to because you know you will not show the level of compassion that the traumatized people deserve. I absolutely believe that the family and friends of James Pouillon, as well as those who witnessed his murder, deserve the best crisis intervention out there. But I have to be honest and say that I could not do this response. As someone who has volunteered to assist at abortion clinics, tangled with anti-abortion protesters, and has a family member who worked at a clinic where people were murdered by an anti-abortion activist, I do not believe I could put that to the side to work with this family. Knowing what he was doing when he was killed and having to in any way validate that would be too difficult for me.

Part of being a good responder is knowing when to say no. I would much rather have a team member bow out then sit down with a victim and judge them, say something inappropriate or break down crying. I would also much prefer it if I could muster the needed skills to be helpful in a situation such as this one. But I know my limitations, and I have to honor mine as much as I honor others. This one, I would have to refer to someone else. I hope there's a team in Owosso more prepared to deal than I.

Eight Years Out

It was a Tuesday. I don't know why I know it was a Tuesday, but I do. The fact that I do tells you the impact that that day had on me, since the only other days of a year or more ago for which I remember the day of the week are the days each of my children were born and the day I was married. And that last one probably shouldn't count, since Jewish weddings are almost always on a Sunday, at least where I'm from.

It was a Tuesday and the kids were lined up for the bathroom when I heard. And when I talked to my husband on the phone I was sitting in the corner of the office looking at a garbage can. I can still see it in my mind. I can hear my daughter's daycare teacher telling me they were closing, and forgetting to tell me who was calling, first. I can still feel -- not just remember feeling, but actually experience feeling -- the brief terror when I heard an airplane go over my house in the afternoon and realized there were not supposed to be planes in the air, and I ran from the third floor of my house to the first before I realized it was an Air Force jet. I can also see the sign on Rita's Italian Ice saying they were closed for the rest of the day. What I remember perhaps even more vividly is putting my daughter, aged 3 1/2 years, to bed a few weeks later and reassuring her that our house was a safe place, that we were safe, and leaving her room and saying, "OK, now she feels safe. Who's going to make me feel safe?"

Absolutely everyone has at least some memories like this. This was a national, group trauma. And while we all experienced it differently, and certainly some of us experienced it much more directly than others, virtually no one over the age of about 13 doesn't remember it, or doesn't thing it affected them.

Trauma violates our worldview. That day violated the notion that many of us still had that this was a safe country, that we were personally not in danger, and that getting up in the morning and going to work was a reasonably safe activity. It happened in specific cities, but it happened in all of our living rooms, to all of us. That was the intent of it in the first place -- to terrorize. It is small wonder that most of us still can have those sensory memories triggered by something or other.

If you think this analysis is overblown, or overly dramatic -- if you think the effect on us collectively was not that great -- consider this. Nowhere in this post have I mentioned what day I remember so vividly. But you all knew anyway.

Stephen Farrell: Survivor's Guilt, Survivor's Anger

New York Times reporter Stephen Farrell was rescued from the Taliban early this morning. He and his translator, Sultan Munadi, had been taken captive in Afghanistan four days before. The raid by British soldiers that rescued Mr. Farrell resulted in the death of both Mr. Munadi, one of the British soldiers and at least two others (news reports conflict about how many and who they were).

Most of us have heard the term "survivor's guilt." It's the guilty feeling that people have when someone else has died in an incident that could have killed them. It's the feeling of the person who called in sick to the World Trade Center on 9-11, or who skipped the exercise class at LA Fitness the night of the shootings, or who survived the accident that killed their friend. I think it's safe to say that Stephen Farrell is, at best, at high risk for feelings of survivor's guilt, both because of Mr. Munadi's death and because a soldier died trying to save Farrell's life.

There's a difficult twist to this episode as well, however. The British went in to rescue Farrell in part because he is a British citizen. His colleague, Munadi, died at least in part because the British initiated the raid, although it isn't clear who fired the shots that killed him. Certainly the British soldier died trying to resuce Farrell. This has the potential to leave some tricky mixed feelings.

On the one hand, Farrell has expressed great thankfulness for his rescue. He is glad to be alive and glad to be free. On the other hand, it has to have crossed his mind that, were it not for him, Munadi would probably not have been abducted and that, were it not for the British coming to rescue him, Munadi might still be alive.

Obviously none of that is Farrell's fault. It also doesn't mean the British military made the wrong call in going in. But it leaves Farrell feeling grateful to the same group that he is, on some level, angry at, and angry at someone who died trying to save him. We can all take a step back and say that all of this was the fault of the Taliban. Farrell probably can too. But the gut feelings following trauma are often not nearly that logical, and Farrell may not just experience survivor's guilt, he may experience survivor's anger, too.

Asa Hill's Legacy

Last Thursday, a seven year-old boy from Buffalo named Asa Hill was critically injured in a car accident. He died on Friday night, and was buried yesterday. Asa's parents have been a couple since high school but were not married. Asa often asked them to get married, and they always told him they would, but it just hadn't happened. Yesterday, at the end of Asa's funeral, his parents finally tied the knot.

This is one of those stories that leaves me speechless. It is fascinating and horrible and touching and sad all at the same time. I don't know what useful box to put my reactions into. And of course, it's not about me, or you, or anyone else, it's about Asa's family. They have to make the choices that are right for them, and it is none of my business to tell them what they should or shouldn't do, let alone second guess their choices after the fact. But it is interesting to think about the pros and cons of Asa's parents' choice to get married when and how they did.

On the plus side, we have the fact that Asa clearly wanted this. Families in mourning often talk about what the deceased would have wanted. In this instance, there wasn't much question that Asa wanted his parents to get married. They may well come to view their marriage as a gift he left behind when he died, and to the extent that they frame it that way that is all for the good. Their decision to marry now also reinforces their commitment to support each other in what has to be the darkest time of their relationship.

On the minus side, it is a frequent mantra of early crisis intervention that you should not make important decisions immediately following a trauma. Action feels better than inaction following a critical incident, and people are prone to do fairly rash things -- buy a house, quit their job, drop out of school, move out of town, etc. -- because at the time it feels like that will help. When the dust settles, often they regret those decisions. I don't know whether Asa's parents really had intended to get married and figured they'd do it now, or made the decision now. If it's the latter, that could be problematic. In a similar vein, it's possible that his parents will not see their marriage as a blessing bestowed by their son, but as a tangible reminder of his death. If so, that can certainly cause difficulty for them down the road.

At least anecdotally, the number of couples who split up following the death of a child is pretty high. Asa's parents' decision to get married under these circumstances could be a move against that trend, or it could make them more likely to be part of that statistic. Time will tell.

In keeping with my personal religious tradition, I hope that Asa's memory is a blessing to his parents and that they know no further sorrow. I also wish them 120 years of happiness in their lives together.

Ready, Set, Swine Flu!

Tomorrow is the first day of school in the great state of Michigan and in many other places. In honor of this, the New York Times is running an article in its "Well" section tomorrow about what parents need to know about H1N1. It's a pretty good article and is full of practical information (e.g. when to call the doctor) placed in reasonable context.

I actually laughed out loud, however, when I read the first few sentences:

A few weekends ago, a mother I know called to ask about swine flu after her daughter complained of breathing trouble and other worrisome symptoms. Fortunately, my friend quickly reached her pediatrician, who reassured her about the child’s condition. But the conversation made me realize just how stressful this flu season is going to be for parents.My first reaction to this was, "Gee, ya think?!? What was your first clue?" How soon we forget the mass hysteria of just 4 months ago, when schools were closing at the first sniffle and emergency rooms were flooded by the not-that-sick and the worried well.

As I've discussed in this space, the quality of information coming from the Centers for Disease Control, the World Health Organization and local health departments has greatly improved since April. The dire warnings are still there, but they are placed in the context of both statistics from seasonal flu and the relative likelihood of the various scenarios. The media, on the other hand, seems, for the most part, not to have gotten the message, and is reporting outbreaks of H1N1 as though they are outbreaks of bubonic plague.

In the midst of all this, we educators are preparing for school and for H1N1. By far the biggest thing we are preparing for, at least in my district, is not death and destruction, it's absenteeism and parental over- and under-reaction. We are quickly getting up to speed on how to post educational activities on the web in ways that parents can access them, making sure that substitute plans are in place, and contemplating what will happen if enough staff are affected that we don't have enough subs to cover them all. We are learning the new mantra -- stay home if you've had a fever of 100 degrees or more in the past 24 hours -- and strategizing what to do about parents who send their children to school anyway. We are making sure all of our staff have the same information so that if an outbreak does occur we can give parents consistent, calm messages.

As laid back as this may all sound, I do have something to admit. When I pause to think about my own friends and family, I am a little stressed. I listen to the cough my son, who has mild asthma, has had for a few weeks and I worry that we missed something, even though I know we didn't. A friend who is undergoing cancer treatment has a suspected case of H1N1, and I not only worry about him but feel personally responsible for nagging him to get to the doctor (I'm sure he appreciates that). Which just goes to show you that preventing panic in others does not prevent stress in oneself. It's going to be an interesting flu season.

Who Owns Your Death?

Lance Corporal Joshua M. Bernard, 21, died in Afghanistan on August 14. An Associated Press photographer embedded with his unit captured a picture of him after he was wounded and before he was transferred to a medical facility, where he died. This week Defense Secretary Robert Gates blasted the AP for publishing the picture, against the express wishes of Bernard's family.

On Friday, my niece's high school notified parents of the death of one of her classmates. Support was offered to students and guidance offered to parents, but no information was shared about the cause of death. The local newspaper reported it was a suicide.

These two events may not seem to have much in common, but in fact they capture a very common problem in traumatic situations. What happens when the powers that be, or just some random witness, have information about a death that the family does not want to share?

There are always two sides to this argument. In the case of Lance Cpl. Bernard, the AP argues that publishing the picture helps the public understand what war is really about. It says it is,

choosing after a period of reflection to make public an image that conveys the grimness of war and the sacrifice of young men and women fighting it.Bernard's family, on the other hand, feels that the publication of the photo inflicts more pain on a family already traumatized and grieving. They prefer not to remember their son that way, and do not want others to see him that way. His father says the photo is disrespectful of his memory.

In cases of suicide, families often want to withhold the fact that their loved one killed themselves. There is a tremendous stigma in our society about suicide. Families often refuse to accept that the victim's death was, indeed, a suicide. Even if they do accept it, they fear that others will look down on them as the family, or will think ill of the dead family member who completed the suicide. It is not at all uncommon for families of those who complete suicide to hear from people trying to be "helpful" that their loved one was selfish or is going to Hell. Not surprisingly, families opt to limit the number of people who have cause to be "helpful" in this way.

On the other hand, from a high school administration point of view (and just generally from a public health point of view), it is important to talk about suicide. While no one wants to destigmatize it to the point where it is considered completely normal and acceptable, community leaders do want to get people talking about the depression and desperation that leads to suicide. The stigma surrounding suicide can prevent those who are contemplating killing themselves from getting the help they need, because they fear people's reactions if they talk about it. In a school setting, often the students know a classmate has completed a suicide, even when the administration does not acknowledge it. Not talking about it when everyone knows about it further sends the message that help is not available, and can lead to the clustering of suicides at high schools that sometimes occurs.

So, what to do? How do you weigh the educational and/or news value of a picture or a piece of information against the legitimate needs of a family in crisis? Whose needs for mitigating critical incident stress win? And whose values should we base that decision on?

We have a strong custom in this society of respecting the wishes of families of the dead. Because of this, violating those wishes provides an easy target for the natural anger that families feel after a traumatic death. I can't say that the AP made the right choice in the death of Lance Cpl. Bernard, even if I wish the family had given permission. They didn't. And I am not convinced that the picture had so much value that it should eclipse those wishes. Luckily, I don't have to make judgements like that most of the time.

As a school administrator and crisis team member, I will not disclose that a death was a suicide without family permission. But I will do two things to try to get around this. The first is that I will explain why I think it is important to share the information. Very often families are willing to hear that their disclosure may help another suicidal person, but they do not make that connection alone. School staff are also often reluctant to share this information, even if they can. We have to educate them about suicide prevention as well.

The second is, if I cannot get permission, to acknowledge when others say they heard it was a suicide. You can talk about it in the abstract even if you can't confirm. So when a child says, "I heard he killed himself" or "the paper says she took pills" I wills say, "I heard that too. If that were true, what do you think about that?" This finesses the whole question of telling when someone's death is a suicide by letting the students tell themselves. The AP could have written a story about the picture without publishing the picture, and explained that the family, who could be kept anonymous, did not give permission. This would have been a chance to talk about the impact of war on families at home, something they chose to gloss over by publishing the picture.

I think the AP, school administrators, and anyone else who has tough decisions to make about sharing or not sharing information, would do well to ask themselves what their ultimate goal is. If it's just to share information for its own sake, that takes you in a different direction than if, as in both of these cases, the aim is to educate. As the saying goes, there is more than one way to skin a cat, and there is more than one way to educate following a traumatic death.

I have chosen not to add the picture that the AP published of Lance Cpl. Bernard after his injury. I hope that the picture above is more in keeping with how the family would like this soldier remembered.

The Georgia Murders

Last Saturday morning, a man called 911 in Brunswick, GA, and said that he had returned home to find 7 members of his family dead and two critically injured. One of the two died on the way to the hospital. The other is still on life support. Today, the caller was arrested for the murders.

It's hard to imagine something more horrific than this. It's difficult to imagine what brings a person to this level of violence, particularly against their own family. It's also hard to imagine how Diane Isenhower, whose ex-husband, four children, ex-brother-in-law and ex-sister-in-law, as well as her daughter's boyfriend, were all murdered and whose grandchild is in critical condition, moves on from something like this. Now her ex-husband's nephew is under arrest. That hardly makes things less complicated.

What particularly caught my attention in the coverage were a couple of comments that various people made about how those affected were coping. Isenhower's brother-in-law, Clint Rowe, expressed concern about the police officers:

They're the ones who walked in on that, so you know it wears on the police as well.I think it's remarkable that a member of this family would think of the police at this moment. It's not that, when you think about it, it's particularly surprising that police officers would be affected by working on a case like this, particularly if they were on scene when the bodies were first found. It's just remarkable that anyone from the family would think of it, given what they themselves are going through.