The Texas Fertilizer Fire

About 10 minutes west of my house, there is a billboard on the highway, courtesy of the Department of Homeland Security. It has a stylized map on it with an arrow pointing to part of it, and it says, "You are here. Where is your family?" It then directs you to the government preparedness website. My family has a little silly ritual we follow every time we pass that billboard. We drive by, I point to the billboard without speaking, and my 11 year-old daughter sighs and says, "Aunt Shirley's house."

About 10 minutes west of my house, there is a billboard on the highway, courtesy of the Department of Homeland Security. It has a stylized map on it with an arrow pointing to part of it, and it says, "You are here. Where is your family?" It then directs you to the government preparedness website. My family has a little silly ritual we follow every time we pass that billboard. We drive by, I point to the billboard without speaking, and my 11 year-old daughter sighs and says, "Aunt Shirley's house."When I tell friends and family this, some of them are somewhat disapproving. They are concerned that by having this conversation with our kids, we are scaring them unnecessarily. They also think that the emphasis on constant vigilance is a little overblown. I do see their points, but at least on that first item -- not scaring the children -- they have it exactly backwards.

It is in fact because of my daughter that we've had many of these conversations. Her temperament has always been such that she confronts things she is afraid of head on and wants to know exactly what "the plan" is if these things should happen. She is the one who insists on having fire drills at home. She has talked through every permutation of stranger danger that there is. She knows that we have a will and have provided for her and her brother if we should die. She likes to know the plan. And while she may be more inclined in that direction than average, kids in general do like to know the plan. Every school in this country is required to practice for a fire, and few argue that we are causing kids to be unnecessarily afraid of fire. In fact, I would argue that we are giving kids a feeling of power over something frightening. We can't make the possibility go away, but we can make them feel like they could handle it if it came along.

I am the first to say that we have been emergencied to death in this country since 9-11. I think we have been encouraged to experience fear for its own sake, and it hasn't helped anyone. However, there is some point to being prepared for bad things happening. There is a level of readiness short of stockpiling a year's worth of food and water and some firearms and ammunition for the coming apocalypse, where we simply ask ourselves what we would do in various circumstances.

I bring this up because the town of Bryan, Texas is very much in need of a plan tonight. There is a major fertilizer fire at the El Dorado Chemical Company and 70,000 people have been told to evacuate. This is absolutely not the sort of thing that most of us are prepared for. If we live in a hurricane-prone area, we usually have a plan for that. If we live near a fault line, we have a plan for earthquakes. If we live in tornado alley, we know what to do when the sirens sound. But very few of us have looked at a map of, say, a five mile radius around our homes and figured out what hazards there are in the factories and businesses near us. Even fewer have considered what is being transported by rail and truck right past our doors.

I bring this up because the town of Bryan, Texas is very much in need of a plan tonight. There is a major fertilizer fire at the El Dorado Chemical Company and 70,000 people have been told to evacuate. This is absolutely not the sort of thing that most of us are prepared for. If we live in a hurricane-prone area, we usually have a plan for that. If we live near a fault line, we have a plan for earthquakes. If we live in tornado alley, we know what to do when the sirens sound. But very few of us have looked at a map of, say, a five mile radius around our homes and figured out what hazards there are in the factories and businesses near us. Even fewer have considered what is being transported by rail and truck right past our doors. However, the lesson of this is not, as you might imagine, that we should all start making a list of things that could go wrong and what we would do about them. The lesson is that we can't possibly anticipate everything that might happen. Therefore, we need to have a generic, all-threat plan. In my family, we don't know what on earth could cause us to have to rendez vous outside of our town, but we know we'll meet at Aunt Shirley's.

Here's the kicker, though. The purpose of having such a plan actually has very little to do with our physical safety. I have no doubt that in an emergency I could grab my kids and find somewhere to go, even if we didn't have a plan. The point of having a plan is to reduce the traumatic stress we experience in the event of an emergency. We will be scared, no doubt. We will be worried about each other until we meet. We will worry about our posessions and our friends. But we will not worry about whether we are doing the right thing, or about generating ideas for what to do, because we have a plan. Just like children, we need to feel power over that which we cannot control, so we've built a little bit of that into our lives ahead of time. We can't prevent traumatic events from occurring, but we can feel a sense of agency when they do, and hopefully that will give us a little bit of leg up when it comes time to recover.

(Check out these additional tips for talking to children about traumatic events)

Vaccine Priorities are Out

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met today and issued guidelines on who should get the vaccine for H1N1 "swine" flu first. As you know, I have strong opinions about how these guidelines, or any guidelines, are going to affect people and how they will be received. So, now that they're out, let's see how we're doing at mitigating the impact up front.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met today and issued guidelines on who should get the vaccine for H1N1 "swine" flu first. As you know, I have strong opinions about how these guidelines, or any guidelines, are going to affect people and how they will be received. So, now that they're out, let's see how we're doing at mitigating the impact up front.I give Day 1 of this process a C-, max. Don't get me wrong -- I don't have any problem with what appear to be the new guidelines. What I have a problem with is that I can find well over 800 articles about them by googling "H1N1 vaccine guidelines," but the guidelines themselves are nowhere to be found.

All 800 articles have roughly the same information: the first wave of vaccinations will go to pregnant women, children and young adults 6 months to 24 years, healthcare workers, adult caregivers of infants and adults under 65 with other medical conditions. If there isn't enough vaccine to accomplish this (since this is about half the U.S. population) they will further pare it down. This information was apparently delivered in a press conference this afternoon. As far as I can find, no press release was distributed, and there is nothing on the CDC website, the government flu website or the ACIP website (in fact, the postings to the ACIP website seem to be running at least a month out of date). You can get the transcript from the Federal News Service -- if you happen to already have a subscription.

In short, the government is relying solely on the press to get the word out. This is pretty much what they did in April and May, and I refer you to my post on the 2009 Flu Pandemic to see how that can go really wrong. You need only look at some of the headlines to see why relying solely on the press is a bad idea. Most news outlets have fairly low key headlines running, like CNN.com, whose headline reads "Federal Panel Issues H1N1 Vaccine Guidelines." On the other hand, we have ABC News, which is running the sensationalist tagline, "Who Gets Swine Flu Vaccine Before You Do?" The government is managing the facts, but not how those facts are presented.

It's probably true that they can't control how the story gets spun. But what they could do, which they aren't, is put out the guidelines in writing on the web so that people who want more information can get it, and so news organizations can link to it. They also could, in the same document, discuss not only why they are making these recommendations, but why those who aren't going to get the vaccine in the first wave should still feel calm. Some detailed, scientific reassurance is in order to frame this as a way of keeping everyone as safe as possible -- after all, an effective vaccination program actually provides some protection for those who have not been immunized, since they are less likely to be exposed.

Once again, the powers that be are failing to understand a basic principle of crisis communication, which is that they not only have to get the information out there, but they also need to anticipate what other information will be out there and where it will come from, as well as how people will react to it. Yes, it's complicated to put out something in writing at the same time as a press conference that is based on a decision that has just been made. But it's not impossible. And they need to get better at it, because with this particular flu, people want their information to be accurate and timely, and timeliness is measured in minutes, not days. And frankly, they really don't have that much time to start getting this right.

(Don't miss the previous Quarterbacking on H1N1)

Trauma Witness and Witness for the Prosecution

The preliminary hearing for the man accused of murdering Dr. George Tiller was held today. He was bound over for trial, to no one's surprise. The CNN coverage of the hearing quotes extensively from the testimony of two ushers who were at the Wichita, KS church where Tiller was also ushering when he was shot on May 31. Some language from their testimony stood out to me.

The preliminary hearing for the man accused of murdering Dr. George Tiller was held today. He was bound over for trial, to no one's surprise. The CNN coverage of the hearing quotes extensively from the testimony of two ushers who were at the Wichita, KS church where Tiller was also ushering when he was shot on May 31. Some language from their testimony stood out to me.Gary Haup, who was standing with Tiller when he was shot, described what happened and then said that what he heard was a "pop."

Keith Martin, another usher, said that he heard a loud noise and saw Tiller on the floor. He said he recognized the man who shot him, but couldn't remember when. He also said that the man

had a horrible smell about him. ... It wasn't just somebody at the gym smell. It was something more, an ammonia-type smell.He testified that the shooter threatened him as he chased him, and that he could see "straight down the barrel" of the man's gun.

These statements caught my eye because they are really vivid. Haup didn't hear "something" he heard a pop. The suspect didn't smell "bad" he had a very specific, unusual odor. And he didn't just see the gun, he "stared right down the barrel."

There are two things going on here. The first is that the prosecutor has almost certainly told these men to be as specific as possible with as much detail as they can remember. That's good prep work with witnesses.

The second thing that is going on here is that these witnesses are remembering vivid detail. That is what happens during traumatic events. When our bodies experience the "fight or flight" response with which we are all familiar, our brains flood with a neurotransmitter responsible for memory. All of our sensory exposure from that instant on is much more likely to be held in memory. We don't just remember what happened, we remember the sensory details. If you've ever been driving along and suddenly had to slam on the brakes because the car in front of you stopped short, you've seen this in action. You can't remember one thing from the second before it happened, but you can remember every little detail right afterward.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. Natural selection favored those animals who could react quickly when faced with a threat -- that's how the fight or flight response evolved in the first place. But it also favored those animals who could identify a threat quickly. In order to do that, they had to learn from their experiences what was dangerous and what wasn't, and how best to react. And in order to do that, they had to keep track of everything they saw, smelled, tasted, felt or heard when something bad happened. That way, when it happened again, they could run even sooner.

The bad news for modern humans is that having heightened senses to perceive danger is not actually all that useful in today's society. Unless you are being shot at with some frequency, remembering what a shooter smells like, for example, is not actually going to help you survive. But it is going to set you up for some troublesome associations, without you necessarily knowing it. The next time Mr. Martin smells someone with that odd ammonia odor, his body is going to shift directly into danger mode, even though he will probably not be in danger.

If this has ever happened to you -- being thrown into overdrive by a smell or a sound that you subconsciously associate with a dangerous or stressful situation -- you probably know that it can make you feel completely insane. The good news, however, is that a) it's typical and b) it usually goes away in a few months. You will still have associations with that sensory experience, but they won't be so complete and alarming.

The good news is also that, if you have to, you'll be one heck of a detailed court witness.

(For additional Quarterbacking on Dr. Tiller's Murder, see The Tiller Family's Critical Incident)

The Ethics of Flu and the Trauma of Ethics

Shortly after 9-11, as the anthrax attacks were starting to unfold, I remember a friend of mine telling me that she had called her doctor to make sure that her smallpox vaccination was up to date and arrange to get a booster. She was quite surprised to learn that not only was such a booster not recommended for her, it wasn't available. There literally was no vaccine out there in the world. When the WHO declared that smallpox had been eradicated back in the 1980's, they stopped manufacturing the vaccine for general use.

Shortly after 9-11, as the anthrax attacks were starting to unfold, I remember a friend of mine telling me that she had called her doctor to make sure that her smallpox vaccination was up to date and arrange to get a booster. She was quite surprised to learn that not only was such a booster not recommended for her, it wasn't available. There literally was no vaccine out there in the world. When the WHO declared that smallpox had been eradicated back in the 1980's, they stopped manufacturing the vaccine for general use. This was surprising to most affluent Americans, because we are generally used to being able to get whatever health care we are willing to pay for. The notion that a technology exists and we can't have it -- not just that our doctors don't want us to have it but that we can't have it -- goes against the way we believe the health care system works. Unlike some aspects of our world view, such as the ones I discussed yesterday involving trauma with children, a lot of people actually believed this one, from our heads to our hearts to our guts, to be true. We really thought we could have any health care that existed. We were wrong.

I suspect we are up against that issue once again, because the medical research community is coming out with a vaccine for H1N1, probably in early October, and there is a good likelihood that there will be more people who want it right away than the initial supply. Over time, the supply will probably increase and everyone can have it, but in the meantime, someone is going to have to decide who gets it. Or, more to the point, somebody is going to have to decide who doesn't. Of course, this isn't news to the powers that be, who issued guidelines and recommendations on this before H1N1 had come on the scene (although it is notable that the United States government flu website still refers to a pandemic declaration as a hypothetical event, despite the fact that it was issued in June).

We've dealt with a shortage of flu vaccine before. In 2004 there was a production quality problem that limited the supply of seasonal flu vaccine, and for several months you could only get a vaccine in the U.S. if you were "high risk." I remember this distinctly because I was pregnant, and hence I could get the vaccine and my daughter could not. But this time will be different, because not everyone wants the seasonal vaccine, and an awful lot more people are going to want this one. An awful lot of people who don't know that "no" is even a possibility are going to be told no.

But it gets worse, because another thing that has kept us relatively calm about H1N1 is that we know that science has advanced in its treatment of respiratory illness. We comfort ourselves that if the 1918 flu pandemic repeats itself, we have ventilators to keep people alive. We also know that health care is more advanced in the U.S. than in most parts of Mexico, so we believe we'll be more "OK" than they were this spring.

There's only one problem. If a pandemic like 1918 comes around again, there very well may not be enough ventilators to help everyone who needs one. The recommendation is that, in a severe and deadly epidemic, ventilators be used only for people who are most likely to survive. Let me put it another way. In the event of a "Spanish Flu"-like epidemic, you could be critically ill and they would not attempt to save you, because giving you treatment would take it away from someone else with a better chance.

I first heard about this charming nugget of information during a training with the public health community in November, before "swine flu" was even in our lexicon. This was the same one, you may recall, at which it was stated that people would not overwhelm ER's because they would be told not to go to the ER. And we all know how well that worked this spring. At any rate, the plan I heard was for only those who were likely to survive to even get to the hospital. Those too sick to have a good chance would be left at the triage center, where they would die. Oh, and I wasn't supposed to tell anyone.

Well, the cat's out of the bag, because the Canadian national newspaper, the Globe and Mail, reported this morning that New York's pandemic working group is recommending removing or withdrawing ventilators by those likely to die during a serious pandemic. So now I can rant publicly.

Don't get me wrong. I get it. I get that we can all only get all the medical care in the world if we have available all the medical care in the world, and that given limited resources we should give them to the people most likely to benefit from them. I also get that that is a complex and difficult line to draw, and that's why we have medical ethicists out there working on this stuff. I am also glad I am not them.

But let's get down to brass tacks. If this pandemic gets bad, particularly in terms of the virulence of the virus, implementing "the plan" is going to be hard. People are going to go to the hospital when we ask them not to. People who are low on the priority list are not going to like that they can't get vaccine. And people are going to get really, really upset when their loved ones are not allowed a ventilator or some other piece of intervention. That is a given. What are we going to do about it?

If there's a plan out there, I haven't seen it. I know in my county that they are including mental health in the planning. They are also aware that the likelihood is that about 80% of us won't be able to respond because of our own illness or illness in our family. If you read the federal guidelines, it looks like perhaps we are in the second tier of vaccination priority, but no mention is made of volunteers, which accounts for an awful lot of us. I fear that once again we are in danger of underestimating the panic and even the rage that is going to occur. All I can say is, I'm ready to be part of the solution and I promise not to be part of the problem. I hope there are a lot of like-minded folks out there.

(For related Quarterbacking, see Getting It Right the Second Time, Flu Preparedness: Body AND Mind, and The 2009 Flu Pandemic)

Corellian Death Rays and Trauma Involving Children

Eight people were killed in a three car accident about 20 miles North of New York City today. Unless you know the people involved, you probably read that and were not particularly affected by it. But it's all in the description. Do you feel differently about this one? Four children, as well as four adults, were killed in a three car accident in New York State today.

Eight people were killed in a three car accident about 20 miles North of New York City today. Unless you know the people involved, you probably read that and were not particularly affected by it. But it's all in the description. Do you feel differently about this one? Four children, as well as four adults, were killed in a three car accident in New York State today.Conventional wisdom tells us that traumatic incidents involving children are harder than those that only involve adults. We all know that instinctively, but why is it true? It all comes down to the ever-present worldview. Most of us hold a set of beliefs on a gut level that are something like these:

- Children do not die

- Parents do not outlive children

- Bad things do not happen to good people

- Children are inherently good

- Parents have the obligation to keep children safe, and we can accomplish that goal

- Short lives are a waste

But with the possible exception of "children are inherently good" (and we can argue about whether short lives are a waste -- I really do not believe they are), none of these things are actually true. And in fact we know they are not true. So why are they so important to us that we lead our lives relying on them being true?

I find myself reminded of the scene in the movie Men in Black where Tommy Lee Jones' character says,

There's always an alien battle cruiser, or a Corellian death ray, or an intergalactic plague intended to wipe out life on this miserable little planet. The only way these people can get on with their happy lives is that they do not know about it!In other words, as you've heard me say before, we base our lives off of what is likely, not what is possible. We choose to ignore what we know to be true -- that tragedy is possible -- because if we lived in the shadow of tragedy all the time we would not be able to live at all. We choose not to know what we know. Until we read headlines like the one today, and we remember.

The Culture of Different Professions

I spent the last 48 hours on an Amtrak train from Chicago to Seattle, courtesy of my 11 year-old daughter, the travel agent. It was spectacular and I highly recommend it, particularly if you have an 11 year old who loves scenery and a 4 year old who loves vehicles of all kinds. This trip should explain my failure to post for a few days.

I spent the last 48 hours on an Amtrak train from Chicago to Seattle, courtesy of my 11 year-old daughter, the travel agent. It was spectacular and I highly recommend it, particularly if you have an 11 year old who loves scenery and a 4 year old who loves vehicles of all kinds. This trip should explain my failure to post for a few days.I spent much of the trip editing Powerpoint slides for the Group Crisis Intervention class I'm teaching for the Ann Arbor Public Schools in August. The International Critical Incident Stress Foundation (ICISF) provides a standard set of over 200 slides, and the approved instructor has the opportunity to edit and rearrange them as long as the content of the class remains the same. In this instance, I was tailoring the presentation for an audience comprised of school personnel.

I came upon the standard slide about the use of peers in CISM, and found myself very disquieted. The slide explains, quite rightly, that using peers -- people in the same profession or of the same background as those receiving the intervention -- is essential when therecipient group is specially trained or educated, the group possesses a unique culture, group members perceive themselves as unique, little understood or misunderstood, or the group extends minimal trust to those outside the group. Then, in the notes accompanying the slide, it says that businesses and schools may not need peers.

Now, I can't speak to businesses because I don't work in a business. I work in a school, and I have my entire adult life. I have never encountered a school or school district that did not fit the above criteria. We may not look like cops. We may not act like firefighters. But we educators have our own culture, are constantly feeling dumped on and distrustful of "top down" initiatives and the community.

I have had the privilege of doing CISM response in many schools as a peer. The need for a peer becomes evident in the first 5 minutes, as the school team starts talking about the pressures of AYP, NCLB and Ed Yes* that form the backdrop for whatever has happened. The CISM mental health professional's eyes glaze over while we talk, and I know that I've formed an instant bond with those with whom we are intervening. I also know that when I sit down with the Principal, who sometimes doesn't feel comfortable receiving support in a group with his or her staff, they almost always say, "I'm fine, I'm just worried about my teachers." And 90% of the time, when I respond, "I know you are, but I also know how hard it is to be in charge of everyone else's needs but your own," they start to talk, and they are not fine. They just think they have to be, and only another Principal has the credibility to understand how hard it is to admit that they're not.

So, at the risk of annoying others who teach this class, I decline to tell those I train that they may not need a peer. In my humble opinion, a peer is something you always want. You may be able to function without one, but you won't be as effective. That's my 2 cents.

*In case you're wondering, those stand for Adequate Yearly Progress, which is a measure mandated by the No Child Left Behind act, and Education Yes is the Michigan State reporting system for this.

Critical Incident, or Just a Crisis?

As you may know, I have Google Analytics installed both on this blog and on the website for my consulting services. This service tracks statistics about visits to the sites, and enables me to generate nifty reports about all sorts of things, such as what browser my readers are using and what state they are in. This morning, I noticed that a visitor to my consulting site from Australia had found my page after googling, "what is the difference between a critical incident and a crisis?" I thought that was a pretty good question, and one that is not, in fact, addressed on my consulting site, so I'm going to try to address it here. Maybe my Aussie fan will google his/her question again and find an answer this time.

As you may know, I have Google Analytics installed both on this blog and on the website for my consulting services. This service tracks statistics about visits to the sites, and enables me to generate nifty reports about all sorts of things, such as what browser my readers are using and what state they are in. This morning, I noticed that a visitor to my consulting site from Australia had found my page after googling, "what is the difference between a critical incident and a crisis?" I thought that was a pretty good question, and one that is not, in fact, addressed on my consulting site, so I'm going to try to address it here. Maybe my Aussie fan will google his/her question again and find an answer this time.When people talk about Critical Incident Stress Management, they often use "critical incident" and "crisis" interchangeably. You will note that I am not the Monday Morning Critical Incident Quarterback, for example, although CISM is what I do and what, for the most part, I write about. But they aren't really 100% the same. Let's look at some definitions.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines "crisis" as "a time of intense difficulty, trouble, or danger."

The term "Critical Incident" is a term of art, and like all good terms of art it is used by two totally different groups to mean two very different things. One way it is used is in the phrase "Critical Incident Technique." According to Wikipedia, in this context a critical incident is "one that makes a significant contribution - either positively or negatively - to an activity or phenomenon." The Critical Incident Technique seeks to study these incidents and how people respond to them to learn how better to respond to future instances.

In the phrase "Critical Incident Stress Management," on the other hand, a critical incident is defined as one which, because of how intense, violent, sudden or frightening it is, has the potential to overwhelm people's usual methods of coping. Critical Incident Stress Management, then, is a technique to help manage the stress that can be, but is not always, caused by critical incidents.

So what's the difference between a crisis and a critical incident? From a CISM perspective, all critical incidents are crises, but not all crises are critical incidents. The current economic crisis, for example, is a crisis for our country, but only a critical incident for some of us. A shortage of Big Macs is a crisis for McDonalds, but probably not a critical incident, at least not for most people. On the other hand, 9-11 was a crisis for the country and a critical incident for large number of people around the country.

So, Aussie person, that's the difference. I hope it helps you and some other readers as well.

The Line of Duty

Detective Mark DiNardo died this morning at 9:35 AM. He was a 10 year veteran of the Jersey City Police Department in New Jersey, and tomorrow would have been his 38th birthday. He leaves behind a wife and three small children. He was promoted to Detective just this past week, but he didn't know it. He was in a coma on life support after he and four of his colleagues were shot while trying to arrest a robbery suspect on Thursday.

Detective Mark DiNardo died this morning at 9:35 AM. He was a 10 year veteran of the Jersey City Police Department in New Jersey, and tomorrow would have been his 38th birthday. He leaves behind a wife and three small children. He was promoted to Detective just this past week, but he didn't know it. He was in a coma on life support after he and four of his colleagues were shot while trying to arrest a robbery suspect on Thursday.There are five types of critical incidents that require a CISM team with special expertise. In fact, there's a whole extra class on them. Death in the line of duty is one of them. Death of a colleague is always hard. Traumatic death of a colleague is worse. But death of a colleague in the line of duty introduces a whole new layer of complexity, both for the surviving colleagues and for the team supporting them.

I started to write this post about what was different about line of duty deaths, but as I reflect upon it, they aren't really different, they are just the usual traumatic themes only moreso. Here are some issues that come up:

- Survivor's Guilt: If I had been [fill in name of circumstance] it would have been me. If I hadn't stopped to tie my shoe. If I had gone in first. If I hadn't called off sick. It should have been me, because my wound was worse, he was a better cop, etc.

- Self-Blame: My job is to protect and serve, but I could do neither for my colleague. If we can't do it for each other, what makes us think we can do it for anyone else?

- Familiarity: I see death and destruction every day. Usually bad guys do it to each other. But this was one of us.

- Anger at the Brass: If we weren't working long hours, if we were properly equipped, if they hadn't let this guy out on bail this wouldn't have happened.

- Identification: What will happen to my wife or husband if this happens to me?

- Self-Doubt: Now I go out on the street and everything makes me jump. What if I can't do my job?

- Keeping it In: If I talk about how this has affected me, they will take me off the street. Besides, cops don't cry.

- Suicide Risk: I can't handle this, and I have a lethal suicide method on my hip all day every day.

In many departments CISM has become required for certain kinds of incidents, usually officer involved shootings and line of duty deaths. There are problems with this -- requirements build resentment, and some people really will do better on their own. But by making it part of what is expected, departments create a way for officers to get the help they need without losing face, and without specifically deciding they need it.

My thoughts are with the men and women of the Jersey City Police Department tonight. Good luck on the journey ahead.

Getting it Right the Second Time

The New York Times is reporting today about efforts in New York City to better manage another outbreak of H1N1 "swine" flu. Not surprisingly, ER's were pretty flooded by the "worried well" in April and May, so they are trying to beef up their triage system outside of the hospitals. They are also instituting new communications plans.

The New York Times is reporting today about efforts in New York City to better manage another outbreak of H1N1 "swine" flu. Not surprisingly, ER's were pretty flooded by the "worried well" in April and May, so they are trying to beef up their triage system outside of the hospitals. They are also instituting new communications plans.This is all welcome news to me and my readers. I have posted twice about the need for better communication and attention to the panic side of the pandemic (see Flu Preparedness: Body AND Mind and The 2009 Flu Pandemic). It looks like New York is thinking in the right directions, and that's all good.

What is surprising, however, is the numbers being cited. Conventional wisdom, based on biological terror attacks such as the Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack in the Tokyo Subway System, holds that anywhere from 80-95% (with 80% being the most commonly cited number) of people seeking medical attention in a public health emergency are either the "worried well" or at best do not need to be hospitalized. However, based on the Times' numbers, on the worst days of the outbreak in May, 40-50 people were hospitalized while an average of more than 1,400 people were seen in the Emergency Room for "flu like symptoms." That means that the "worried well" and the not very sick accounted for about 96.5% of those going to the ER.

For those of us who have prepped for disaster with the so-called "80-20 rule" (80% of people will be worried well, while 20% will be actually ill), this is a sobering statistic. What it means is that we have vastly underprepared for people's level of panic about this disease, and the triage plans that even the most prepared jurisdictions have might not be enough.

Unless, of course, we get better at communicating and more directive about who should do what. Telling people that the symptoms include "fever," for example, is not going to be enough. Public Health authorities are going to need to say,

If you do not have a fever higher than X [and I leave it to them to determine what X is] you do not have the flu. Do not come to the triage center.Note how I phrased this. It will not be enough to say not to come to the triage center. They need to say why. Doing so will increase credibility and make people listen more. It won't be perfect, but it might tamp things down to that 80-20 ratio. Because if it's going to be 96-4 and we have a major outbreak, our health system is in deep trouble.

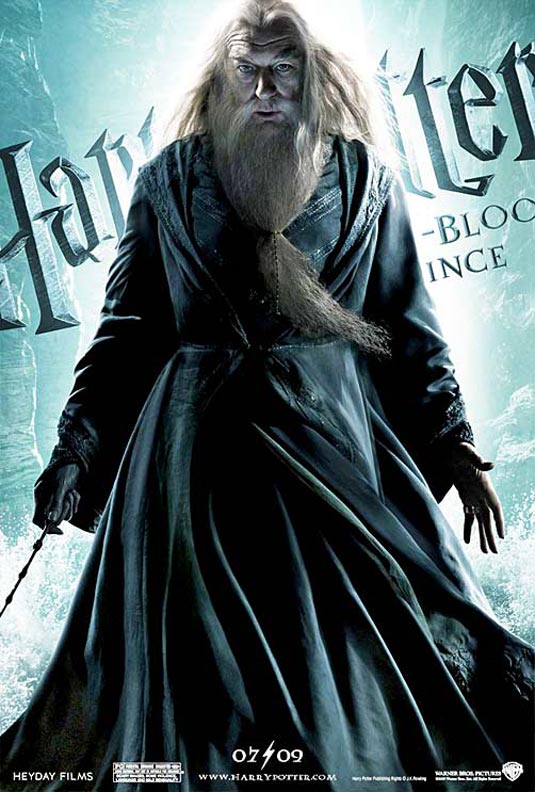

Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince: A Picture is More Traumatizing Than a Thousand Words

This week I took my 11 year old daughter to see "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince," better known in my house as "the 6th movie." To say that she is a Harry Potter fan would be to greatly underestimate her complete immersion in the books and the previous 5 movies. She was an early reader, and I read her the first book in early 1st grade. She read the rest of them herself, including finishing the final book in less than two days (after, of course, staying up with me until midnight and dressing in character to pick up our two copies at the bookstore the day it came out). She has probably read the 6th book the equivalent of 50 times, when you include all the going back and rereading favorite parts in addition to reading the whole thing. She has never been the slightest bit scared of anything she read.

So on Wednesday when we went to the movie on opening day, I was rather surprised by the sounds I heard coming from the chair next to me. She was scared. Not terrified to the point of needing to leave, but really scared. She was whimpering, curling her legs up in her chair, and shaking during the scary parts. But she loved it, and as I write this she's off with her father seeing it again.

Why was the movie so very much more terrifying to her (and to me, by the way) than the book? It's not like she didn't know what was going to happen or how it would end. She's certainly old enough to know that it's fiction. Why was her reaction so extremely different between the movie and the book, or even between this movie and the previous five movies?

I think there are two things going on here. The first has to do with the means of receiving the story. When you read a book with no pictures, it is up to you to "see" the story for yourself. Some people do much more of this than others when they read, but all of us do it to some extent. We imagine what the scene looks like as it is described. Our brains are really pretty good at preventing us from "seeing" things as being particularly frightening. We have an internal censor that just blips past the scariest images. We know they happen in the book, but we don't experience them as intensely because our brains won't let us. When we see a movie, however, we don't have the luxury of toning down the frightening parts. Someone else, not our own brains, has made the images, and they're not adjustable based on how scared we are. In a film, we have the sensory experience of whatever is frightening to us, not just the imagining of it.

The sensory exposure issue ought to be the same for all the movies, however. The scariest parts to every movie are scarier than the scariest parts of the corresponding book. Was this book really that much more scary than the first five? Yes, but not for the reasons you might think. To a true Harry Potter lover, Dumbledore is very real. Yes, my daughter knows he's fictional, but he is a very beloved character. She was genuinely sad when he died in the book. Watching the movie, anticipating that he was going to die, elicited an emotional reaction that didn't exist in any of the previous movies. She was not as attached to Sirius Black, who dies at the end of the fifth book/movie, or Cedric Diggory in the 4th, and all the other ones she knew that "everything comes out all right in the end." That isn't true in this movie. Everything is not all right in the end. It was scary, and in the end it was going to still be scary and sad. Knowing that removed one of her best tools for consoling herself.

I'm not sorry I took her to see this movie. She isn't having nightmares about it or otherwise dwelling upon it and, as I mentioned, she wanted to see it again. I suspect the second time will be a little easier, because she'll have seen it all before. But it does serve as a reminder to all of us that there are things that are better read about or listened to than seen, and when in doubt we should probably be protecting all of us, not just our children, from unnecessary sensory exposure to violence and tragedy.

And That's the Way it Is: Walter Cronkite (1916-2009)

But I'd like to take this opportunity to talk about Cronkite, not just because he was an American icon and a big part of my childhood (as was Michael Jackson, by the way), but because he was a pretty good crisis communicator.If you've never seen the footage of Cronkite announcing the death of President John F. Kennedy, I encourage you to do so now. I will date myself and say that I was not alive when Cronkite did this broadcast, so I can't claim it holds sentimental value for me, but I found it quite touching.

From a crisis communication standpoint, Cronkite does a lot of things right in this clip. He acknowledges the rumors that are out there, and he labels them rumors. He tells us that it is hard to get good information. When new information seems to come in that is simply the same rumors, he tells us that. And when confirmation finally comes that the President has died, he tells us in a very straightforward manner, and shows his emotions in a reasonable way. He then begins to move on to the next piece of information we are almost certainly wanting -- where is the Vice President? Except perhaps for the last few seconds, he engages in absolutely no speculation. He does not talk about "what if" scenarios. He sticks to the facts and he is clearly sharing them in real time.

If you've ever been watching TV as major news breaks, you know that Cronkite's style is pretty different from what we can expect on news today. Perhaps the most egregious example I can recall is when TWA Flight 800 exploded over Long Island and Dan Rather in less than an hour had declared that it was quite obviously a bomb. I have no interest in getting into the debate about what brought down Flight 800, but it was not "obviously" anything. News organizations like to "scoop" each other, and guessing right in a crisis has great rewards. Nobody thinks about what happens if you guess wrong.

Can you imagine if any of the myriad news stations were covering the JFK assassination now? Certainly we'd have various experts talking about gunshot wounds and the types of surgeries people have for them. We'd be shown old file footage of the President, the car he was riding in, that street corner in Dallas, and various kinds of rifles. The crawl underneath would tell us every minute detail of everything that anyone was saying about the situation, and the caption under the reporters would read "Breaking News: President Possibly Dead." Oh, and the anchor wouldn't be taking off and putting on his glasses, and you certainly wouldn't hear someone talking to him on camera.

Walter Cronkite reaped the benefit of being straightforward and honest, sticking to known facts and not holding back on them, and managing rumors when he was named the "Most Trusted Man in America" in repeated polls. He was a good example for all of us.

And that's the way it is . . .

Why Us?: The Jakarta Hotel Bombings

I had some insomnia last night, and happened to be online at 4 AM. It's a good thing, because otherwise I might well have missed the news that two suicide bombings in Jakarta, Indonesia had targeted the Ritz-Carlton and Marriott hotels. At that hour, the death toll was listed as eight and rose to nine while I was reading, but now is being reported as six. By the time I woke up after finally falling back to sleep, the story was no longer the top one. Now, at 3:30 PM, it isn't even in the list of top stories at CNN.com.

I had some insomnia last night, and happened to be online at 4 AM. It's a good thing, because otherwise I might well have missed the news that two suicide bombings in Jakarta, Indonesia had targeted the Ritz-Carlton and Marriott hotels. At that hour, the death toll was listed as eight and rose to nine while I was reading, but now is being reported as six. By the time I woke up after finally falling back to sleep, the story was no longer the top one. Now, at 3:30 PM, it isn't even in the list of top stories at CNN.com. This story raises two interesting questions. First, why did terrorists target these particular hotels? And second, why did we lose interest so quickly?

It seems obvious, but the goal of terrorism is to induce terror. The Broadway show Wicked has the wonderful line, "As terrifying as terror is . . . " The entire point is to make people afraid of what will come next, to make them look over their shoulders and alter their routine, and to ultimately make them decide that they would rather give in to some set of demands than continue to live in a constant state of fear.

In order for this to be successful, the terror has to be induced in those who are in a position to give in to the demands. There is no sense, for example, in making me scared in an attempt to get your mother in Cleveland to let you stay out past curfew, particularly if I don't know you or your mother. On the other hand, there may be some purpose in making me scared in an attempt to get me to let my own children stay out past curfew, or even to pressure my best friend into letting her kids stay out.

The answer as to why these hotels were targeted lies in the particular aims of the terrorists. Since no information is available as yet, at least in the mainstream media, about who is responsible, we can only surmise that either the perpetrators have a beef with western countries, most likely the United States (these were American-owned hotels where westerners stay) or believe that those countries are in a position to pressure others to do what they want. If their issue were more localized, we could expect they would be bombing marketplaces or other venues where Indonesians congregate. Clearly, the aim here was not to scare Indonesians. It was to scare us.

So why did we lose interest? Sometimes stories are pushed off the front page by more pressing stories, but today there is no single "big story" on major media websites. Quite frankly, we lost interest because we were not terrified enough, and we were not terrified enough because these bombings were not events we could personally identify with.

At 4 AM these bombings were big news because they were new and it was not clear they were over. Someone was trying to kill westerners and damage western property, and westerners, through their proxies in the media, were scared. But by 3:30 PM it was clear that while Americans had been wounded, none had been killed. No more explosions had occurred. And honestly, the vast majority of Americans feel absolutely no connection to Indonesia. Probably relatively few can even locate it on a map, and we have some vague idea that Indonesia is a place where bombings just happen. Our reaction would be vastly different if the exact same scale of attack occurred on U.S. soil. If the headlines at 4 AM could be translated as, "Someone is trying to kill us!," the coverage now boils down to, "They didn't kill us, and besides, it wasn't really us."

I'm sure that if you are in the habit of traveling to Indonesia, and certainly if you tend to stay at those hotels, this is still a big story. That's because, for that subset of the American population, the personal connection is much stronger. For the rest of us, we go back to judging what is likely vs. what is possible and decide that this really doesn't have much to do with us. For all our protestations that we care about all human life and suffering, we care about it a lot more when we can connect it to ourselves.

Put On Your Own Mask First

I recently exchanged emails with the coordinator of our county CISM team. I had been approached to assist an acquaintance who recently was in a serious car accident, and I was checking in with him before doing so. Think of it as analogous to a police officer being asked to investigate a crime -- you wouldn't just go off and do that without notifying your commanding officer, no matter how wonderful you think you are. The following is a piece of the reply I received:

I recently exchanged emails with the coordinator of our county CISM team. I had been approached to assist an acquaintance who recently was in a serious car accident, and I was checking in with him before doing so. Think of it as analogous to a police officer being asked to investigate a crime -- you wouldn't just go off and do that without notifying your commanding officer, no matter how wonderful you think you are. The following is a piece of the reply I received:I think that one of the areas leaders in CISM can have a positive impact on others is encouraging and role modeling good self care. From what I’ve observed, you may have some growing to do in this one area.He then proceeded to caution me about the risks of responding to incidents that affect me or with which I might particularly identify.

I thought that was one of the most carefully and diplomatically worded pieces of constructive criticism I have ever received. Someone a little less tactful, such as, say, me, might well have written, "When will you ever learn? You really stink at knowing when you are too close to a situation." I appreciated the skillful word-craft.

So, in the interest of having a positive impact on my readers, here are some thoughts on self-care. My coordinator might add that you should do as I say, not as I sometimes do!

As my regular readers know, secondary trauma is a big risk for those who work in trauma response. I often describe it like this: Trauma is a steaming pile of manure (OK, I don't use the word manure, but this is a family friendly blog). When you help someone who has been traumatized, you help them shovel their manure. But there's only so much manure you can shovel without getting some on you. At some point, you have to stop and take a shower.

Now that you all have that lovely visual image . . .

It's true, though. Other's trauma traumatizes us. Every single CISM team member should be taking good care of their body, mind and spirit after every single response. There is no such thing as, "I don't need to, I'm fine." There is only, "I need to" and "I really need to." What that self-care looks like is highly individualized, but it closely mirrors what we advise for the traumatized people themselves: get exercise; eat healthy food; access your support network of friends, family and faith; do more of whatever you do to decompress (because ironically the more stress we are under the less we feel like doing the things we know help us); steer clear of alcohol and drugs; give yourself time.

I have never been bad at doing those things. What I'm really bad at is recognizing when I need to step back altogether. Because I am passionate about this work, I have strong opinions about how it is done. It's hard to care that much and then say that I myself will not be doing it. I once likened it to watching someone else parent your child -- it's hard not to be involved. But I also know, even if I need to be reminded, that when an event impacts me or my school community or the people I love significantly, I just can't be part of the response.

When airlines do the demonstration of oxygen masks before takeoff, they remind you to put on your own mask first and then help others. The same goes for crisis response. We're no good to anybody until we're good to ourselves, and sometimes that means referring incidents to someone else.

There, does it seem like I've done some growing in this one area?

You Can't Contain the Facts: The Murder of August Provost, Part 2

To refresh your memory, Provost was murdered while standing sentry. He was shot three times, bound, gagged, and set on fire. He was African-American and, depending on which report your read, either gay or bisexual. He complained of being harassed by fellow service members, and his family believes his murder was a hate crime. The Navy, on the other hand, has said there is no evidence of a hate crime and referred to this murder as a "random act of violence."

The way the Navy has chosen to deal with this situation is unfortunate, and is probably making things worse for both themselves and the family. It turns out that when the Navy notified Seaman Provost's family of his death, they told them he was found unconscious on sentry duty and later died. They failed to mention that he was murdered, let alone share the details. Provost's mother found out he had been shot and burned from the television coverage.

This violates some very, very basic principles of how institutions should behave in a crisis. I wish I could say it was unusual, but unfortunately it is all too common. Institutions -- whether it's a school, the military, a business or the government -- like to clamp down on information. We have this naive notion that all that will become public is what we say, so we don't say much.

But facts exist whether we talk about them or not, and they have a way of making it into the public arena. Instead of asking, "What facts do we want people to have?" institutions should be asking, "If we don't share this fact, how will it look when it does become public." It's almost always better for people to hear bad news immediately, directly and completely.

The two rules I always share with staff in my school and other schools about sharing bad news with children are very simple:

- Tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth (which also means no guessing) and

- Make sure that every known fact they will hear comes from you, and that no rumors do.

The minute you violate either of those rules, no matter how well-meaning you are, you lose all trust and credibility, and the same rules go for adults. As soon as it is known that you withheld information, gave inaccurate information or left facts to be revealed by the media or the rumor mill, no one will trust what you say and you will be completely ineffective in being supportive following the incident. People naturally want to blame others following an incident, and you will be the target whether you deserve it or not.

I wonder how this situation would have played out if the Navy had told the family how Seaman Provost died, had acknowledged the possibility of a hate crime even if they didn't think it was one, and had been honest with the Congressman on the base that day. I have to imagine that there would be a whole lot fewer conspiracy theories floating around.

The Pros and Cons of a Military Smoking Ban

Last week, a report by the Institute of Medicine recommended that the United States Military move towards being smoking-free over the next 20 years. On the face of it, the reasons to do this seem pretty straightforward. Given that the American taxpayer will be picking up the health care costs for most members of the military indefinitely, it is certainly in our best interests to have these folks stop smoking. Also, since people who smoke get sick more often with respiratory infections and the like, eliminating smoking among our soldiers improves military readiness.

Last week, a report by the Institute of Medicine recommended that the United States Military move towards being smoking-free over the next 20 years. On the face of it, the reasons to do this seem pretty straightforward. Given that the American taxpayer will be picking up the health care costs for most members of the military indefinitely, it is certainly in our best interests to have these folks stop smoking. Also, since people who smoke get sick more often with respiratory infections and the like, eliminating smoking among our soldiers improves military readiness.It certainly seems to make sense for the military to stop subsidizing tobacco on military installations. There's no reason for the military to be encouraging people to smoke, and studies do show that increased prices on tobacco products reduce use.

However, the Quarterback, an avid non-smoker and smoke-hater, has some mixed feelings about banning smoking in the military outright. Don't get me wrong, I'm all for soldiers not smoking. I wish nobody smoked. And if we could guarantee that no person in the military ever started smoking, I'd be all in favor of that. To the extent that we can do things, like stop subsidizing cigarettes, that will discourage people from starting smoking in the first place, we definitely should.

But let's take a look at some of the statistics from that report. Thirty-two percent of members of the military smoke, compared to 20% of the general population. Soldiers on deployment are twice as likely to smoke as those stationed stateside.

To what do we attribute this? Part of it is what the report refers to as "the image of a tough, fearless warrior," who, one presumes, smokes. But I think that is missing a rather major point.

Nicotine is a drug. We all know that. When we talk about it as a drug, we are usually talking about it's addictiveness -- and it sure is addictive. But it also is a drug the same way valium or xanax is a drug -- it calms you, and may actually combat cognitive dysfunction in people with mental illness. In fact, a 2000 Harvard study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association estimated that mentally ill people, who are 4-8% of the population, account for more than 44% of all cigarettes sold in this country. In short, people use nicotine to self-medicate. That is why deployed soldiers smoke more than non-deployed ones. When stress goes up, so does tobacco use. Soldiers in battle are traumatized, and they are using nicotine to ease the psychological effects of that trauma.

And who is the person most likely to turn to a cigarette to ease stress in a war zone? Well, smokers, obviously. But a close second would be former smokers. People who have been addicted to cigarettes and who know what effect they have psychologically start wanting cigarettes under stress. The question is, how bad do we think that is?

The Quarterback recently responded to the scene of a suicide. The deceased's buddies were standing around outside the apartment, and we asked them what we could get for them in terms of food and drink. They asked for hamburgers, cigarettes and a keg. We got them the first two, but not the keg. It is well-established practice in CISM to discourage substance use and abuse following trauma. But what about cigarettes? At least one of these guys had quit smoking the month before. It just didn't seem like the time to argue about it.

On the one hand, discouraging smoking is, as a general rule, a good thing. On the other hand, I worry about having a bunch of soldiers who quit smoking to join up walking around a battle zone unable to smoke and jonesing for a cigarette like mad. I don't know what the right answer is. The Quarterback welcomes your comments.

The Other Survivors of Train Accidents

Four families (two of the dead were siblings) are in a state of shock and anger and disbelief this weekend. Friends, classmates and people who live near the track are also traumatized. The situation is further muddied by the fact that the driver had had his license suspended just the day before. Plenty of blame and anger is being thrown around, I'm sure.

But there is one person you might not be feeling for today, and maybe you should. What about the train's engineer?

The statistics about railway fatalities are pretty stark. In 2007, there were 856 people killed in railroad incidents in the United States. Of those, 339 were at railroad crossings. The vast majority of fatalities -- 630 -- were what are called "trespasser fatalities." Those are people on the tracks, either at the crossing or elsewhere, who should not have been there (this accident was not a trespasser fatality, since the car was trying to cross the tracks, not sitting on them). There are no official statistics on how many of those trespasser fatalities were suicides, but the number is high.

The Quarterback had the pleasure, at a recent conference, of getting to know a gentleman who works in the Employee Assistance Program at Amtrak. I asked him what the chances were that any given engineer would be involved in an incident in which the train struck and killed someone during his career. My colleague said, "If you stick with the job, it will happen to you, possibly more than once." In fact, Amtrak includes pre-incident inoculation -- preparing people for such an accident -- as part of its education of new train crews.

The fact of the matter is, if someone is on the tracks who shouldn't be, or crossing the tracks when it's not safe, there is nothing the engineer can possibly do to stop the train in time. With the power of operating an enormous, fast machine like a train, comes the knowledge that in fact the train is more powerful than you. What an awful part of the job to have to "get used to."

We've all heard people joke about, or maybe even discuss seriously, throwing themselves under a train or a bus. We rarely stop to think that when someone does that, intentionally or not, they also force the operator to kill them. So this evening, I'm taking a moment to think about my new acquaintance and the men and women he works with, and the engineer who will have to live with this experience for the rest of his or her life.

Flu Preparedness: Body AND Mind

We were discussing plans to set up "triage centers" around the county. The idea was that, in a major health emergency, hospital resources would be used solely to treat the very sick. Because we know that roughly 80% of people who seek health care in these situations are actually the "worried well," we don't want those people overwhelming hospital emergency rooms. By setting up remote centers, health professionals can figure out who is actually sick and send them to the hospital, those who are panicked but not sick can get some support, and the hospital can concentrate on healing. The media would be used to let people know that they should go to their triage center, not the ER. Great.

The Quarterback, being an impudent sort, asked what seemed to me like an obvious question: What are you going to do about the people who go to the ER anyway. The response? People will be told not to go to the ER. But what about the people who do? They will have been told not to.

I bring this up, because the Department of Health and Human Services had a big flu preparedness summit yesterday, and kicked off a public contest to create a relevant Public Service Announcement on preventing the spread of influenza. The Quarterback tries, really tries, not to be cynical, but I can't help but think that for all we learned from our practice run back in April with H1N1 "swine" flu, there's a lot we still haven't learned. I have ranted at some length in a previous post about the failures of communication and the failure to take mental health into consideration this spring. The message may be cleaner and smoother now, but it is still pretty much the same.

The stance of the Obama administration seems to now be that if we tell people "Don't panic, just prepare" and we give them things to do to prepare, they won't panic. It's not that there's no truth to this. Panic is in part caused by a feeling of powerlessness, and giving people something useful to do combats that feeling. As my regular readers know, our minds desperately want to feel like the situation is under control, and certainly being useful helps with that.

But that's not all our minds need. Our minds need good information, and our minds need to feel heard. It is all well and good to tell us not to panic. Many if not most people won't, just as most people won't go to the ER if we tell them to go to a triage center. But just as we have to have a plan to deal with the people who come to the ER anyway, we have to plan for those who are panicking when they don't need to.

In the Quarterback's humble opinion, it would help the panicking folks a lot to hear, "We totally understand why you might be anxious about this. We are confident that we are ready, and here is why. If you are feeling really anxious, here are some things you can do to help yourself and your family deal with the stress." We know some people are going to overreact. Are we ready to deal with them preemptively as well as reactively?

The administration is telling schools to get ready to be "significantly impacted." As someone in the front lines of that battlefield, the Quarterback appreciates the heads up. But mostly what they are talking about is preparing for school closures, significant student and staff illnesses, and possibly administering vaccine on site. That's all important, but that's not what I'm preparing for right now. While the nurses at school work on that side of things, I'm thinking about how we can best prevent panic among our parents and staff. Last year, we had parents asking if we were going to stop serving tacos in the lunch room (which is both racist and incredibly, incredibly stupid) and teachers refusing to teach kids who had vacationed in Mexico. Telling those people not to panic is not going to be enough. Telling them what to do about their panic might help.

Steve McNair, Sahel Kazemi, and the Woulda Shoulda Coulda Game

Sahel Kazemi killed Steve McNair and then herself sometime early Saturday morning. The Quarterback has already delved into how incredibly messy this situation is for McNair's wife, and how the blame game is so hard to play but so compelling at these moments. Now we've added another level.

Sahel Kazemi killed Steve McNair and then herself sometime early Saturday morning. The Quarterback has already delved into how incredibly messy this situation is for McNair's wife, and how the blame game is so hard to play but so compelling at these moments. Now we've added another level. One of my CISM mentors is fond of saying that when there's a suicide, there's always a lot of "woulda shoulda coulda," as in, "If only I woulda paid attention. I shoulda taken her seriously. I coulda stopped her." Once again, as our minds desperately try to make sense of a senseless situation, we try to come up with a plausible way that this event could have been stopped. We do this because we want to believe that we can protect ourselves from it happening again, to us or someone else. The problem is that often, as we weave our theories about what could have been done differently, we wind up blaming ourselves, if we are close to the person who completed the suicide, or, if we are not as close, we blame those who are.

In this situation it seems pretty clear that Kazemi told some folks she was thinking of killing herself. She told a friend her life was a mess and "I should end it." This leaves the obvious question, what did the friend do with that information? We don't know, and we're not going to know. Whatever it was, I'm sure the friend is doing a whole lot of woulda shoulda coulda right now.

But let's take this out of the context of suicide. Let's suppose, for the sake of argument, that you are standing on a busy street corner when a fellow pedestrian walks past you and into the street. You see a car coming at them, and in a flash the car has hit them. Are you responsible? I think most people would say you are not, although you would feel horrible and guilty and traumatized. Was there more you could have done? Maybe. Maybe you could have yelled, or pushed the person out of the way, or thrown yourself in front of the speeding car. And it's entirely possible none of that would have made a difference. And maybe it would have. There is a big difference between missing a possible opportunity to avert a tragedy and being responsible for it in the first place.

When someone has decided to kill themselves, there are absolutely things you can and should do to try to stop them. At the same time, if they complete the act of suicide, it is their responsibility. That's a tension that's hard to deal with, but it's true.

The Quarterback would be remiss, however, if she did not remind you of some simple things that you, no matter who you are or what your background or training is, can do to try to prevent someone from killing themselves:

- Take it seriously. No, not everyone who talks about "ending it" means they are going to kill themselves, but it's better to overreact than underreact.

- Ask the question. There is a myth out there that if you ask someone if they are contemplating suicide they might get the idea from you. No one has ever killed themselves because they were asked. If you're worried, ask very directly, "Have you been thinking about killing yourself." If the answer is yes, that person needs to be seen by a mental health professional, period.

- Call the suicide hotline at 1-800-273-TALK. There are also national and local hotlines listed in your yellow pages and on the web. If you're not sure what to do about someone you think may be a danger to themselves, call.

- Don't try to handle it alone. Friends can be the most helpful by getting the suicidal person the help they need. Don't leave the person alone until you can connect them with professional help.

The Intersection of Crisis Response and . . . Pretty Much Everything

" Referring to the recent crash on the D.C. Metro that killed 9 people, he wrote:

" Referring to the recent crash on the D.C. Metro that killed 9 people, he wrote:The relative rarity of air and rail disasters makes them novel, and hence news. Car crashes bite man, and rail and air crashes bite dog. Intensive coverage of the few air and rail accidents that do occur in turn promotes the widespread — and erroneous — inference that planes and trains are unsafe. In an unfair irony, in transportation perhaps too much safety can be a dangerous thing.The Quarterback brings this up because in a recent post about the murder of Neda Sultan, I wrote:

We live our lives based on what is likely, not what is possible, in terms of danger. This video brings home in a very vivid way what of course we already knew -- that the world is not safe, particularly if you are a protester in Tehran.But Morris brings up the flip side of that, which is that trauma messes with our understanding of what is possible vs. what is likely. When something like this happens, we feel like we've been duped. We've been living our lives in a state of complacency, believing, say, that the Metro is safe, and we feel like all of a sudden we have woken up from our stupor to the horrible truth that it really isn't. And the media coverage reinforces that false perception.

On a related note, on Monday Freakonomics posted the following:

In the 1990’s, a call went out for the F.A.A. to stop letting air-traveling parents carry young children in their laps, making them buy a ticket for their children instead, so that every person could wear a seatbelt. The F.A.A. refused, saying that the cost of an extra ticket could force parents to travel by car instead. Car crashes are the leading cause of death for children. On the other hand, the problem of child safety in air travel, the F.A.A. said, “barely exists.” Yet another example of how terrible we are at assessing risk, especially when it comes to our children.One of the commenters replied:

The response to your blog is simple . . .The overwhelming majority of people are ignorant of the scientific method — thus, probability and risk.

I can't tell you how strenuously the Quarterback disagrees with this analysis. The fact that rational information tells us something different than that upon which we feel compelled to or choose to act does not mean we don't understand better information, or how good information is obtained. It just means that there are things that are psychologically more compelling than empirically derived data in this instance, and that, as the original post notes, we are actually pretty bad at estimating what the empirically derived data on danger will tell us.

Morris understands this when he looks at how the relative rarity and the news coverage of a transportation accident skews our perception of the danger of that mode of transportation. It may be that if you ask people which is safer, a car or the Metro, they will say a car. They will be wrong. But I doubt that if you told them the relevant statistics most people would say, "No, the Metro is still more dangerous." What they will say, however, is, "Even though I know that, my gut instinct is just to avoid the Metro."

Our guts are powerful, and yes, they are influenced by data and by the scientific method. They are also influenced by media coverage, shock, personalization, and perhaps most powerfully, by what we can control. We can avoid a plane, or strap our child in. We can avoid the Metro. We can drive defensively. But what most of us can't do without completely changing our entire lives is avoid driving, so it is important to us that, on a gut level, we continue to be able to drive. We therefore ignore that data, perhaps not cognitively, but instinctively. We're not stupid, we're just trying to get by, to live in the shadow of what is likely and what is possible.

Trigger: It's Not Just for Roy Rogers Anymore

Recently, she told me that while she enjoyed reading this blog, she thought she might have to stop, because it triggers her. If you've never been triggered you may not have the first clue what it means. Once you have been, you don't have any doubt that that's what it was.

Recently, she told me that while she enjoyed reading this blog, she thought she might have to stop, because it triggers her. If you've never been triggered you may not have the first clue what it means. Once you have been, you don't have any doubt that that's what it was.Simply put, when someone is triggered, they suddenly feel the emotions and physical sensations of something really awful -- often something really awful from their past, but not always -- because of some association with the present. People with PTSD of course are more easily triggered and their reactions when they are triggered can be much more severe. But really, anyone can be triggered, and sometimes the connections can be quite tenuous.

I will use myself by way of illustration -- I don't know of anyone else who has volunteered to have their personal trauma reactions exposed to public scrutiny. One of the standard things that instructors warn you about when you take classes in Critical Incident Stress Management is that some scenario or other that is being used in a practice exercise may trigger you. So I'm going to warn you that I'm about to share a scenario that triggered me, and encourage you to take a deep breath, maybe have some tea, because it might well trigger you.

Last summer I took the Strategic Response to Crisis class at an ICISF regional conference. The practice scenarios in this class all build on one another. First there's a car accident in a small town. Then there's a leak at the chemical plant, causing the town to be evacuated. Then a school administrator completes a suicide, and it turns out he was responsible for part of the evacuation in which someone died. Then some kids on a hiking trip get lost in the mountains, and a rescuer falls over a cliff. In our class, we joked that this town was about as safe to live in as the fictional town of Cabot Cove, Maine was in the old TV series Murder She Wrote.

About the third or fourth scenario involved a panicked mother coming up to a roadblock during the evacuation and saying she couldn't reach her babysitter. Sure enough, the sitter had missed the evacuation notice, and both she and the baby were dead. When we reached that part of the script, there was a collective gasp and sort of a thud feeling in the group. And there was that same thud in my gut. Something must have shown in my face, because my instructor, the incomparable Doug Mitchell, asked if I was OK. I said, "This is a hard one for me" and he told me to take a walk. (As an aside, I went to the ladies room and Doug came to find me and sent someone in to drag me out. I enjoy telling people that Doug Mitchell once followed me into the ladies room.)

It wasn't that anything like this had ever happened to me or anyone I knew. It just represented the worst fear I had ever had as a parent. The fact that it had happened, even fictionally, represented on some level that it actually could happen, and my panic and all the associated emotions just flooded me. Doug did that which we do -- he walked and talked with me for a bit and told me I was normal, these things happen, and then I went back to class.

The thing I want to highlight here is that he told me I was normal. There are different ways people like to phrase this message, and different phrasings that different people like to hear:

- What you're going through is pretty typical for people in your situation

- You're having the normal reactions of a normal person under abnormal circumstances

- I'd be worried about you if you weren't feeling a little off

- I often hear that from people who have gone through something like this

Personally, I prefer the very professional wording, "You're not crazy." And I figure that between 80 and 90% of what I do in crisis intervention is deliver that message. People under stress feel like they are losing their mind. Reassurance that they're not goes a long way.

Which brings me back to my friend, and her triggering. Triggering is a real phenomenon. It happens to most people at some point in their lives, whether they have PTSD or not. So, if you ever read anything in this blog that triggers you, or causes secondary trauma even to the slightest degree, let the Quarterback preemptively tell you that you're not crazy (well, you might be, but this isn't evidence of it). Give yourself a break, do what you need to do to feel better, and don't feel like you have to read the rest of the post. I'll live.

Anger and Trauma: Two Great Tastes that Taste Great Together

Imagine, if you can, that your husband and father of your children doesn't come home one night. He's done this before, and you hate it, but you live with it. He's not home the next day, either, which is a little strange and you're starting to get worried. Then, in the afternoon, the doorbell rings and a police officer tells you that your husband has been murdered. What would your first reaction be?

If you said, "disbelief," "that can't be true" or "how do you know?" you're probably right. The mind is amazingly good at protecting itself, and the sudden death of a loved one is something it needs to deal with a piece at a time. There are some messages we don't accept delivery on right away.